A Deeper Look at Zero-Cost Proxies for Lightweight NAS

25 Mar 2022 | deep-learning automated-machine-learning architecture-searchImagine you have a brand new dataset, and you are trying to find a neural network that achieves high validation accuracy on this dataset. You choose a neural network, but after 3 hours of training, you find that the validation accuracy is only 85%. After more choices of neural networks — and many GPU-hours — you finally find one that has an accuracy of 93%. Is there an even better neural network? And can this whole process become faster?

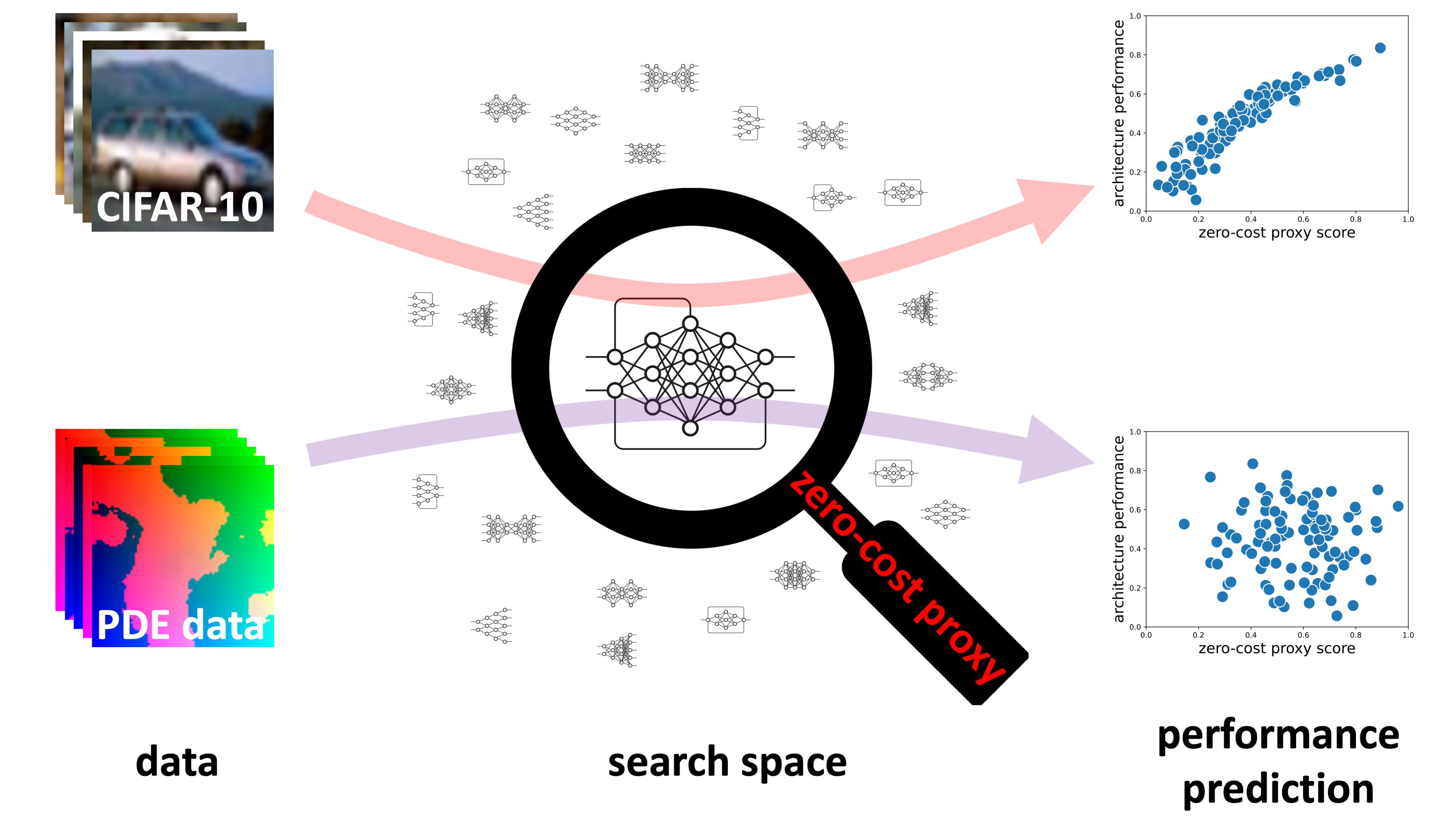

These questions are central to the main challenges of neural architecture search (NAS), an area of research which seeks to automate the discovery of the highest-performing neural networks (with respect to a chosen combination of accuracy, latency, etc). NAS has been used recently to achieve state-of-the-art performance in a variety of tasks (Zoph and Le 2016, Liu et al. 2018, Real et al. 2018, Elsken et al. 2018), but NAS techniques often take notoriously many GPU-hours to train. In 2020, one of the most novel papers in the field was released: Neural Architecture Search without Training by Mellor et al. This paper promised to give an estimate of the validation accuracy for a given architecture in just five seconds. It spurred a flurry of follow-up papers (e.g., Park et al. 2020; Chen et al. 2021; Li et al. 2021; Lin et al. 2021; Lopes et al. 2021), notably, including the ICLR 2021 paper Zero-cost proxies for Lightweight NAS by Abdelfattah et al., which is the focal point of our blog post. Abdelfattah et al. assembled a variety of zero-cost proxies (ZC proxies) inspired by the pruning-at-initialization literature and demonstrates their effectiveness. Furthermore, via their experiments on NAS-Bench-101, -201, -ASR, and -NLP, it can be considered the gold standard in this sub-area as of ICLR 2021. Their release of thorough and reproducible code for their evaluations was critical to our blog and demonstrates the importance of such public repositories for furthering NAS research.

But, do zero-cost proxies really work? Has this line of work truly come up with meaningful indicators of architecture performance, or do simple baselines such as “number of parameters” perform just as well, as claimed in two recent papers?

In this blog post, we take a deeper look into ZC proxies for NAS. We survey prior work on ZC proxies and then run new experiments using the recent NAS-Bench-360 and TransNAS-Bench-101 benchmarks, which give a much more diverse set of datasets and tasks than all prior work. We make the following conclusions:

- Across a wide range of tasks, there is no single ZC proxy which performs significantly better than the others.

- ZC proxies still require further research since “FLOPS” and “number of parameters” are consistently competitive baselines, and data-agnostic ZC proxies tend to perform very inconsistently.

- ZC proxies show great promise when used in conjunction with other methods such as one-shot training or model-based prediction, to improve the performance of these existing NAS techniques at very little additional cost.

Overall, we provide a landscape overview of this promising area, highlight strengths and weaknesses, and shed light on future research in this direction. The rest of this blog post is organized as follows:

- Background and Related Work

- Evaluation of ZC Proxies on Diverse Tasks

- Cases For and Against Zero-Cost Proxies

- Conclusions and Future Directions

Background and Related Work

To make sure we’re all on the same page, we start with a bit of background on NAS, ZC proxies, and the search spaces we consider later.

Neural architecture search (NAS)

Given a dataset and a large set of neural architectures (the search space), the goal of NAS is to efficiently find the architecture with the highest validation accuracy (or a predetermined combination of accuracy and latency, size, etc.) on the dataset. For a survey of the different techniques used for NAS, see Elsken et al. (2018) and Wistuba et al. (2019). Many NAS methods make use of techniques to predict the final performance of a neural network before it is fully trained (Domhan et al. 2015; Wen et al. 2019; Ning et al. 2021; Ru et al. 2021). While these methods are much better than fully training each architecture to completion, they still require nontrivial computation time. For example, learning curve prediciton may be used on an architecture trained to 20 epochs, to estimate the performance at 100 epochs. But in search spaces containing hundreds of thousands of architectures, an even faster estimate would be beneficial.

Zero-cost (ZC) proxies

Zero-cost (ZC) proxies were designed by Mellor et al. (2020) to give an extremely quick estimate of the performance of architectures. The method computes statistics from a forward pass of a single minibatch of data. At five seconds, this method was essentially “zero-cost” compared to all other performance prediction techniques at the time.

Since the original work in 2020, at least 20 new ZC proxies have been proposed.

Our blog focuses on the ICLR 2021 paper, Zero-cost proxies for lightweight NAS by Abdelfattah et al., which assembles a variety of ZC proxies inspired by the pruning-at-initialization literature and demonstrates their effectiveness, both separately and via ensembling, on standard NAS benchmarks. Before analyzing Abdelfattah et al., we give a brief overview of the extant methods in the field.

There are many ways one can categorize ZC proxies;

for example, one can start with the original application of the measures used, grouping those such as snip (Lee et al. 2019), grasp (Wang et al. 2020), and synflow(Tanaka et al. 2020) that were originally proposed for parameter pruning—i.e. “guessing lottery tickets”—together to separate them from those introduced directly for NAS such as NASWOT (referred to as jacob_cov by Abdelfattah et al.).

Another reasonable taxonomy is the justification behind these methods, e.g. whether they are largely empirically-inspired such as grad_norm (Abdelfattah et al. 2020, taking the gradient norm of a randomly initialized architecture after one minibatch) or Blockswap (referred to as fisher by Abdelfattah et al.), or the range of “theory-inspired” measures such as grasp, TE-NAS (Chen et al. 2021), and NNGP-NAS (Park et al. 2021) that use recent attempts to understand deep nets via limiting-case kernel approximations to construct ZC proxies.

While we do examine methods across all these categories, an experimental focus of this blog post is in answering the following question: do these ZC proxies work consistently across a diverse set of datasets and tasks, when the search space is fixed? As a result, the most relevant taxonomy of these methods is the extent to which they actually use the training data of any given dataset to make predictions. Here we have two distinct groups of ZC proxies:

- Data-independent. We define this group of ZC proxies to be those that entirely ignore the dataset, or use it only to set dimensions.

Despite the fact that they are by definition incapable of customizing architectures to the data distribution at hand, multiple data-independent ZC proxies such as

synflowandGenNAS(Li et al. 2021) have been published in top conferences in the past year. Their use on their own requires assuming the existence of near-universal architectures that work for any task; of course, they may also be used in conjunction with other NAS methods to universally bias a search space before fine-tuning to a specific task. Either approach requires at least a decent correlation between data-independent scores and task performance on any dataset. We also consider the natural data-independent baseline —params— which simply counts the number of weights in the network. We summarize the data-independent ZC proxies below.GenNAS— This technique uses a series of synthetic proxy tasks to estimate the architecture’s ability to capture different types of sine frequencies, scale invariances, and spatial information (Li et al. 2021).params— number of parameters in the network.synflow— Synaptic Flow was introduced as a pruning-at-initialization technique that takes a product of all parameters in the network (Takana et al. 2020). Later it was used as a ZC proxy (Abdelfattah et al. 2021).Zen-Score— This technique approximates the neural network by piecewise linear functions conditioned on activation patterns and computes the Frobenius norm, re-scaling to account for batch norm (Lin et al. 2021).

- Data-dependent. This category is defined to be those ZC proxies that use the data to compute the scores but do not make gradient updates to the network weights.

This covers the majority of ZC proxies, including theory-inspired ones (

grasp,TE-NAS,NNGP-NAS) and various heuristic measures (grad_norm,snip,jacob_cov,fisher). While in principle these measures can often use the entire dataset — e.g.grad_normcould sum the gradient across all datapoints andTE-NAScould compute statistics of the full kernel matrix — in practice usually only one minibatch is used. Thus, while these measures do not entirely ignore the data, they nevertheless do not make full use of it to score deep nets, making it necessary to check whether their usefulness is indeed maintained when using a different type of data. Here we also have a natural baseline —flops— the number of flops it takes to pass the input through the network.EPE-NAS— This technique measures the intra- and inter-class correlations of the prediction Jacobian matrices (Lopes et al. 2021).fisher— This technique was introduced as a pruning-at-initialization technique (Turner et al. 2020) and later used as a ZC proxy that computes the sum over all gradients of the activations in the network (Abdelfattah et al. 2021).flops— number of flops to pass the input through the network.grad_norm— This technique sums the Euclidean norm of the gradients (Abdelfattah et al. 2021).grasp— This technique was introduced as a pruning-at-initialization technique that approximates the change in gradient norm (Wang et al. 2020). Later it was used as a ZC proxy (Abdelfattah et al. 2021).jacob_cov— This technique measures the covariance of the prediction Jacobian matrices across one minibatch of data (Mellor et al. 2020).NASI— This technique estimates the performance by approximating the neural network as a neural tangent kernel (Shu et al. 2022).NNGP-NAS— This technique approximates the Neural Network Gaussian Process using Monte-Carlo methods as a cheap measure of performance (Park et al. 2020).snip— This technique was introduced as a pruning-at-initialization technique that approximates the change in loss (Lee et al. 2018). Later it was used as a ZC proxy (Abdelfattah et al. 2021).TE-NAS— This technique analyzes the spectrum of the neural tangent kernel and the number of linear regions in the input space (Chen et al. 2021).

ZC proxies have been applied to existing NAS methods such as Bayesian optimization (White et al. 2021, Shen et al. 2021) and differentiable architecture search (Xiang et al. (2021)), which we discuss in the Cases For and Against Zero-Cost Proxies section below. Since the initial release of this blog post, several new works on ZC proxies have been released (Chen et al. 2021; Wu et al. 2021; Shu et al. 2022; Javaheripi et al. 2022; Zhou et al. 2022; Mok et al. 2022; Zhou et al. 2022).

NAS-Bench search spaces, datasets, and tasks

Now we describe the search spaces, datasets, and tasks that we use for experiments in the next section.

- NATS-Bench. NATS-Bench is a popular cell-based search space for research. It has two different search spaces: (1) Topological Search Space (NATS-Bench-TSS) consisting of 6466 non-isomorphic architectures (15625 total) trained on CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and ImageNet16-120. This is identical to its earlier version named NAS-Bench-201. (2) Size Search Space (NATS-Bench-SSS) which includes 32768 architectures which differ amongst each other in the size of each stage in the cell-based skeleton. We use the NATS-Bench-TSS search space in our experiments.

- DARTS. The DARTS search space is the most widely-used search space in NAS research. It consists of $10^{18}$ architectures. The search space contains two kinds of cells, each with seven nodes: “normal” and “reduction”. The edges between each node can take one of eight operations and each node can take in inputs from two other nodes.

- TransNAS-Bench-101. TransNAS-Bench-101 is a tabular NAS benchmark which consists of two separate search spaces: a micro search space of size 4096, and a macro search space of size 3256. All architectures on each search space are evaluated on seven different computer vision-based tasks from the Taskonomy dataset. The tasks include object classification, scene classification, unscrambling the image (jigsaw), and image upscaling (autoencoder). We use the micro-level search space, which is similar to NAS-Bench-201 but with 4 choices of operations per edge instead of 6.

| $\quad\quad\text{Raw Image}\quad\quad$ | $\text{Object Classification}$ | $\text{Scene Classification}\;$ | $\quad\text{Jigsaw Puzzle}\quad$ | $\quad\text{Autoencoding}\quad$ |

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 1: Diverse tasks from TransNAS-Bench-101 based on Taskonomy used in our experiments.

New datasets

The NATS-Bench and DARTS search spaces have already been used in prior work to evaluate ZC proxies, but we introduce several novel datasets to ZC proxy evaluation by making use of NAS-Bench-360 and recent synthetic data.

- Spherical CIFAR-100. Natural planar images from CIFAR-100 are projected onto a hemisphere with random rotations to create spherical signals, each 60 X 60 pixels across RGB channels. Spherical images are highly relevant to application areas such as omnidirectional vision and weather modeling.

- NinaPro DB5. The NinaPro dataset consists of electromyography (EMG) wave signals to be classified into 18 categories. The signals are converted into single-channel 2D matrices, on which CNNs have achieved state-of-the-art performance.

- Darcy Flow. Darcy Flow refers to a family of partial differential equations (PDE), and the task is to learn the mapping from input conditions to their solutions, which acts as an efficient replacement of traditional solvers. This dataset requires the network to output a 2D grid of the same size as the inputs; the specific setting in NAS-Bench-360 is the lowest-resolution problem considered by Li et al. (2021).

- Synthetic CIFAR-10. This dataset is a drop-in replacement for CIFAR-10 with the same image resolution of 32x32, 3 channels, 50000 training and 10000 test images. It was designed by Dey et al. (2021) to test the performance of ZC proxies. The images are sampled from a random Gaussian distribution, and their class membership labels are determined by passing the images through 10 randomly initialized neural networks and picking the label to be the ID of the neural network that had the maximum output response to the image. We include this dataset in our repertoire to study whether the content of data itself has an effect on the performance of ZC proxies.

| Spherical CIFAR-100 | NinaPro DB5 | Darcy Flow | Synthetic CIFAR-10 |

|

|

|

|

Figure 2: Diverse datasets from NAS-Bench-360 and synthetic data used in our experiments.

Evaluation of ZC Proxies on Diverse Tasks

We evaluate ZC proxies on (1) the NATS-Bench and DARTS search spaces using NAS-Bench-360 and synthetic datasets, and (2) the TransNAS-Bench-101 search space with four vision-related tasks, both of which include a diverse set of tasks, are novel to ZC proxy research, and stand in contrast to the de rigueur over-reliance on image classification in current NAS literature. Furthermore, by evaluating the same search space over different tasks, we can evaluate whether data- and task-independent ZC proxies like synflow suggest ranks which are universal in nature.

We evaluate the six ZC proxies used in Abdelfattah et al., as well as two baselines, for a total of eight methods.

For the NATS-Bench and DARTS experiments, we use Archai, while for the TransNAS-Bench-101 experiments, we use NASLib. Both NAS frameworks have permissive open-source licenses, and we release fully reproducible source code and datasets with this blog post (for any questions related to reproducing our results, please contact Colin or Debadeepta. We randomly draw a fixed set of architectures from each search space (1000 for NATS-Bench and DARTS, 100 for TransNAS-Bench-101), and evaluate each ZC Proxy metric for each architecture. Then, for each ZC proxy, we compute the Spearman’s rank correlation between the proxy and the validation accuracy when fully trained.

On NATS-Bench TSS, we run experiments on three different datasets: Spherical CIFAR-100, CIFAR-100, and Synthetic CIFAR-10. Since Spherical CIFAR-100 and Synthetic CIFAR-10 are not part of the original NATS-Bench tabular benchmark, we also trained each of the 1000 architectures on these datasets following the protocol laid out in the NATS-Bench paper (SGD optimizer, 200 epochs, cosine decay learning rate from 0.1 to 0, 0.9 momentum, 256 batch size). On the DARTS search space, we run this experiment on five different datasets: Spherical CIFAR-100, CIFAR-100, Synthetic CIFAR-10, Darcy Flow, and NinaPro. These datasets span image classification, EMG wave signal classification, and PDE solving. We trained the set of 1000 randomly sampled architectures on all five datasets, closely following the NAS-Bench-301 protocol (100 epochs, batch size 96, number of cells 8, momentum 0.9, cosine learning rate from 0.025 to 0.001). On the TransNAS-Bench-101 search space, we evaluate on four different tasks from the Taskonomy dataset: object classification, scene classification, jigsaw (image unscrambling), and autoencoder (image upscaling). We obtained the final performance of each architecture on each task from the TransNAS-Bench-101 API.

Table 1: Spearman’s rank correlation between each ZC proxy and ground-truth evaluations for NATS-Bench Topological Search Space (TSS).

| Proxies | NATS-Bench TSS Spherical CIFAR-100 |

NATS-Bench TSS CIFAR-100 |

NATS-Bench TSS Synthetic CIFAR-10 |

|---|---|---|---|

fisher |

0.0745 | 0.6104 | -0.4281 |

grad_norm |

0.0056 | 0.6779 | -0.3140 |

grasp |

0.0327 | 0.6319 | -0.2568 |

jacob_cov |

-0.2512 | 0.7194 | 0.1988 |

snip |

0.0075 | 0.6789 | -0.3194 |

synflow |

0.1758 | 0.7938 | -0.0004 |

flops |

0.0239 | 0.7142 | -0.0701 |

params |

-0.0017 | 0.7346 | -0.0426 |

Table 2: Spearman’s rank correlation between each ZC proxy and ground-truth evaluations for DARTS.

| Proxies | DARTS Spherical CIFAR-100 |

DARTS CIFAR-100 |

DARTS NinaPro |

DARTS Synthetic CIFAR-10 |

DARTS Darcy Flow |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

fisher |

0.4986 | -0.0161 | -0.1181 | -0.1685 | 0.1540 |

grad_norm |

0.2450 | 0.2669 | -0.1436 | 0.0105 | 0.1788 |

grasp |

-0.4754 | 0.2301 | 0.0107 | 0.0523 | -0.0970 |

jacob_cov |

0.3538 | -0.1337 | 0.0277 | -0.1235 | -0.1232 |

snip |

0.2675 | 0.2303 | -0.1458 | 0.0234 | 0.1419 |

synflow |

-0.0560 | 0.3935 | -0.1729 | 0.0552 | -0.3978 |

flops |

-0.2074 | 0.5625 | -0.1085 | 0.2635 | -0.1971 |

params |

-0.2389 | 0.5630 | -0.0888 | 0.2644 | -0.2275 |

Table 3: Spearman’s rank correlation between each ZC proxy and ground-truth evaluations for TransNAS-Bench-101.

| Proxies | TransNAS-Bench-101 Jigsaw |

TransNAS-Bench-101 Object Classification |

TransNAS-Bench-101 Scene Classification |

TransNAS-Bench-101 Autoencoder |

|---|---|---|---|---|

fisher |

0.4361 | 0.7998 | 0.7522 | 0.5611 |

grad_norm |

0.4933 | 0.7286 | 0.6756 | 0.4380 |

grasp |

0.5085 | 0.6233 | 0.5034 | 0.4646 |

jacob_cov |

0.3733 | 0.3969 | 0.6964 | -0.1569 |

snip |

0.5367 | 0.7582 | 0.7162 | 0.3671 |

synflow |

0.4853 | 0.6331 | 0.7582 | -0.0850 |

flops |

0.5161 | 0.5686 | 0.7360 | 0.0650 |

params |

0.5068 | 0.5614 | 0.7181 | 0.0517 |

Across Tables 1-3, we see a diverse set of ZC proxies achieving the best performance for each task.

On NATS-Bench TSS, synflow and jacob_cov perform the best.

Notably, on the synthetic dataset, all ZC proxies are negatively correlated with accuracy, except for jacob_cov.

On DARTS, all of the ZC proxies are relatively balanced. fisher, grad_norm, grasp, and params each perform the best for at least one dataset.

Finally, on TransNAS-Bench-101, we also see a mix of performances. snip and fisher perform particularly well.

Across all search spaces, we see that the data-independent ZC proxies, synflow and params, tend to perform very well on some tasks, and very poorly on others.

This is because for each search space, they give a universal architecture ranking, which cannot generalize across tasks.

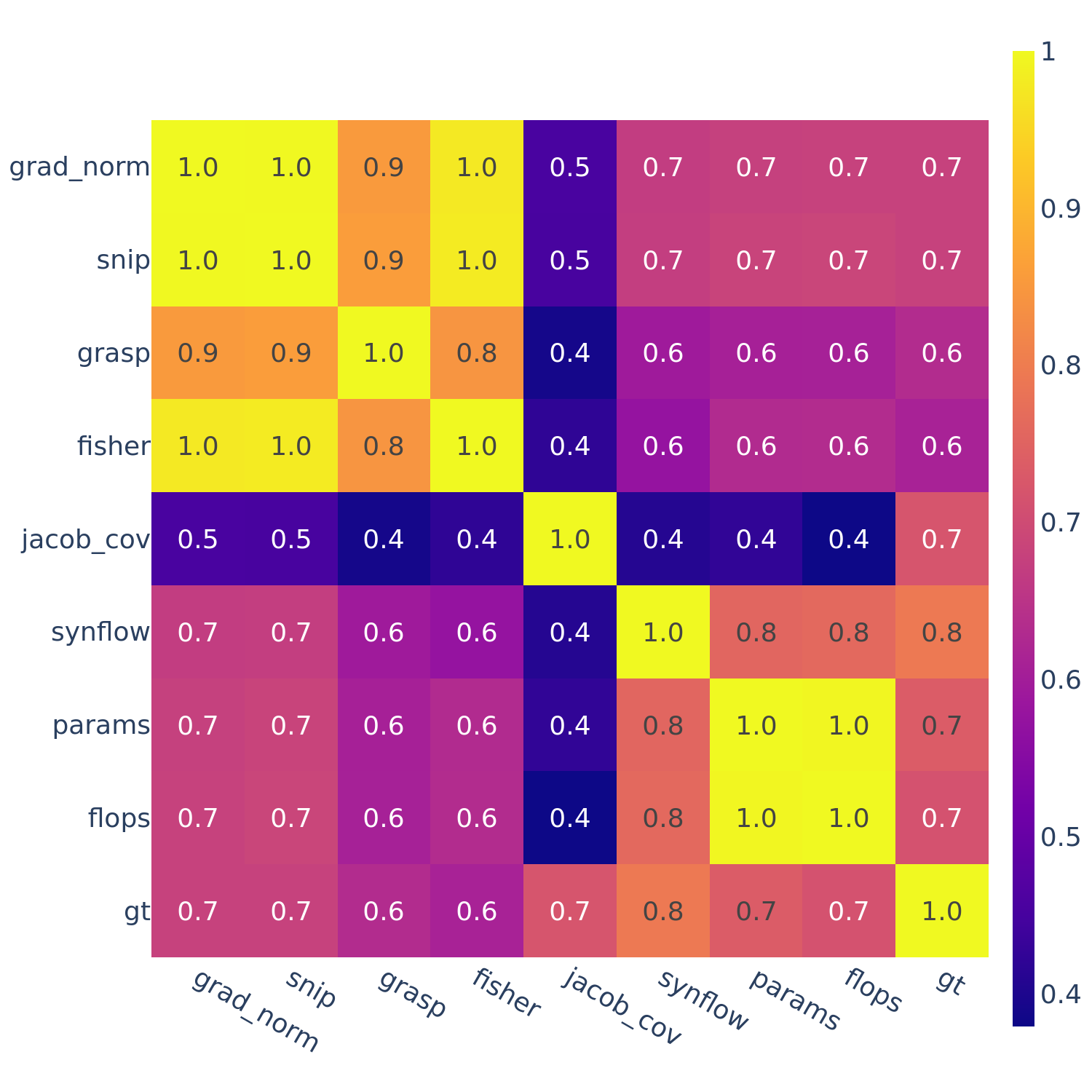

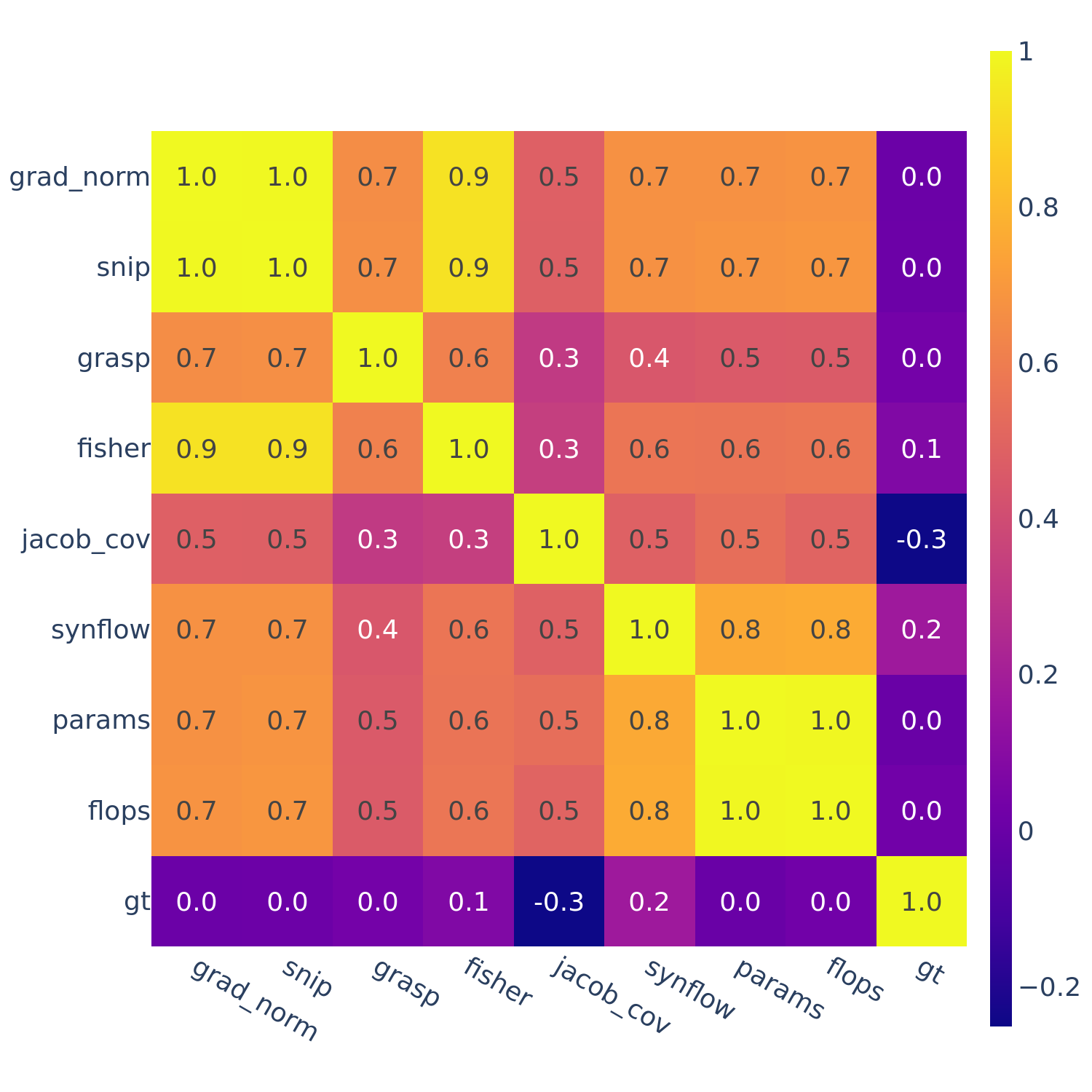

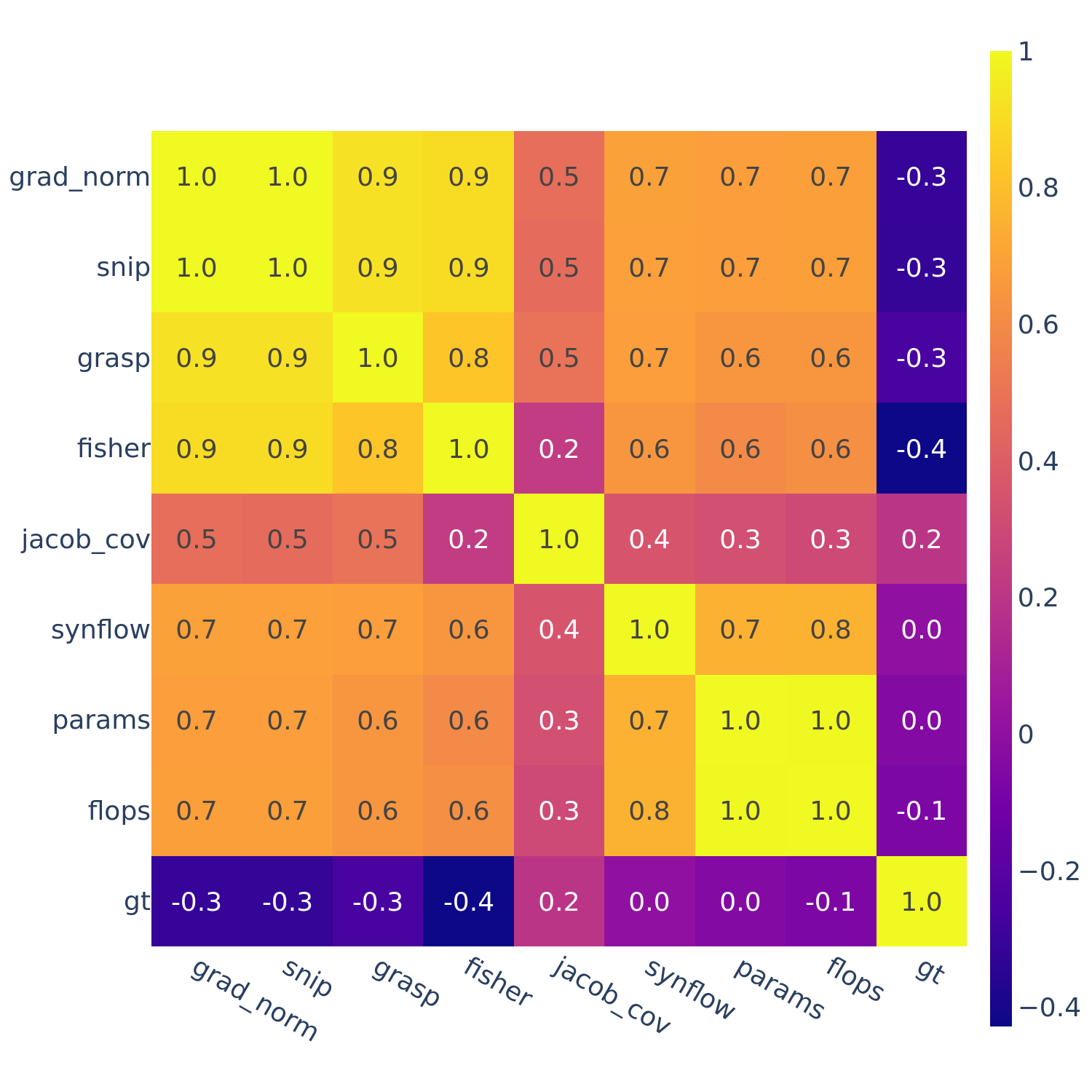

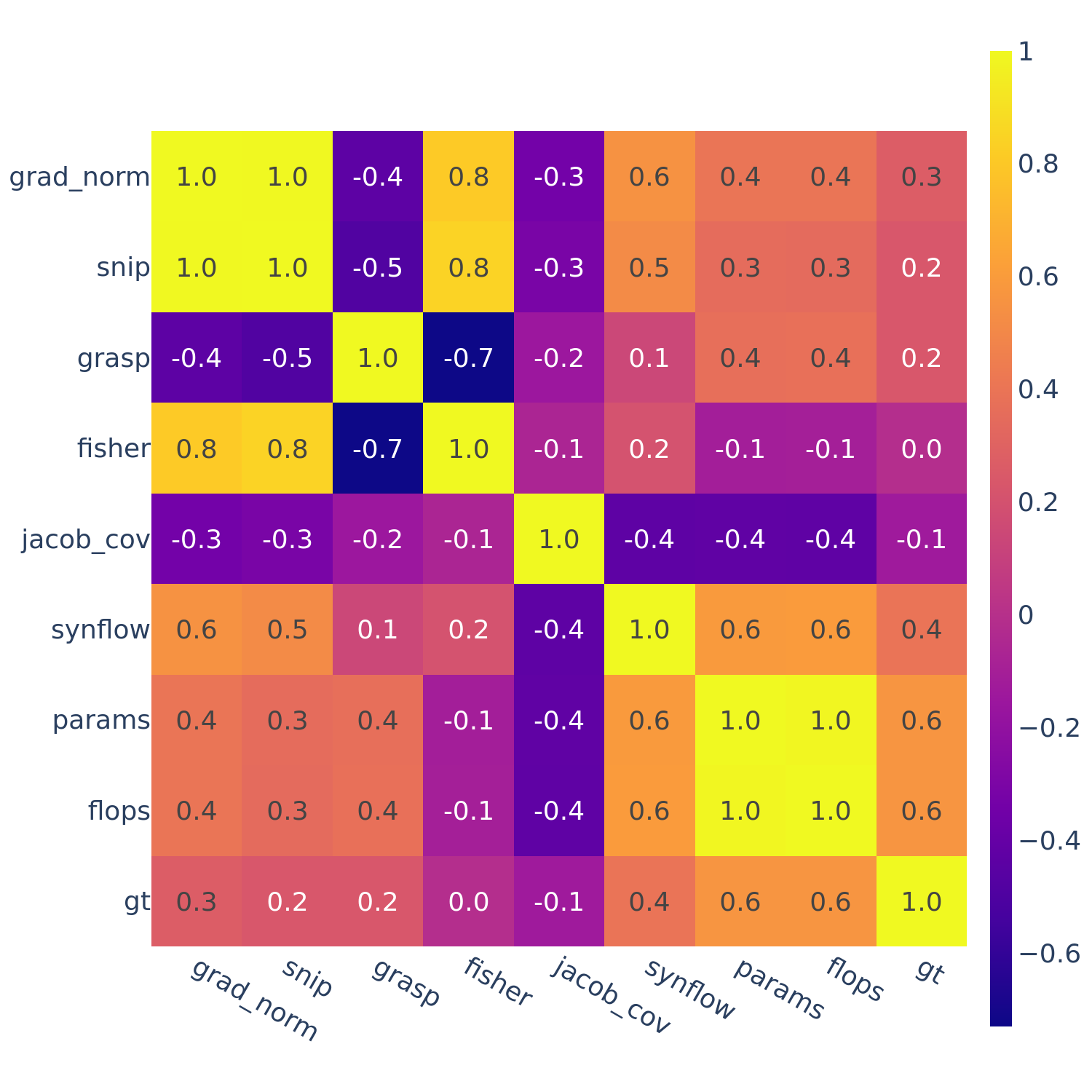

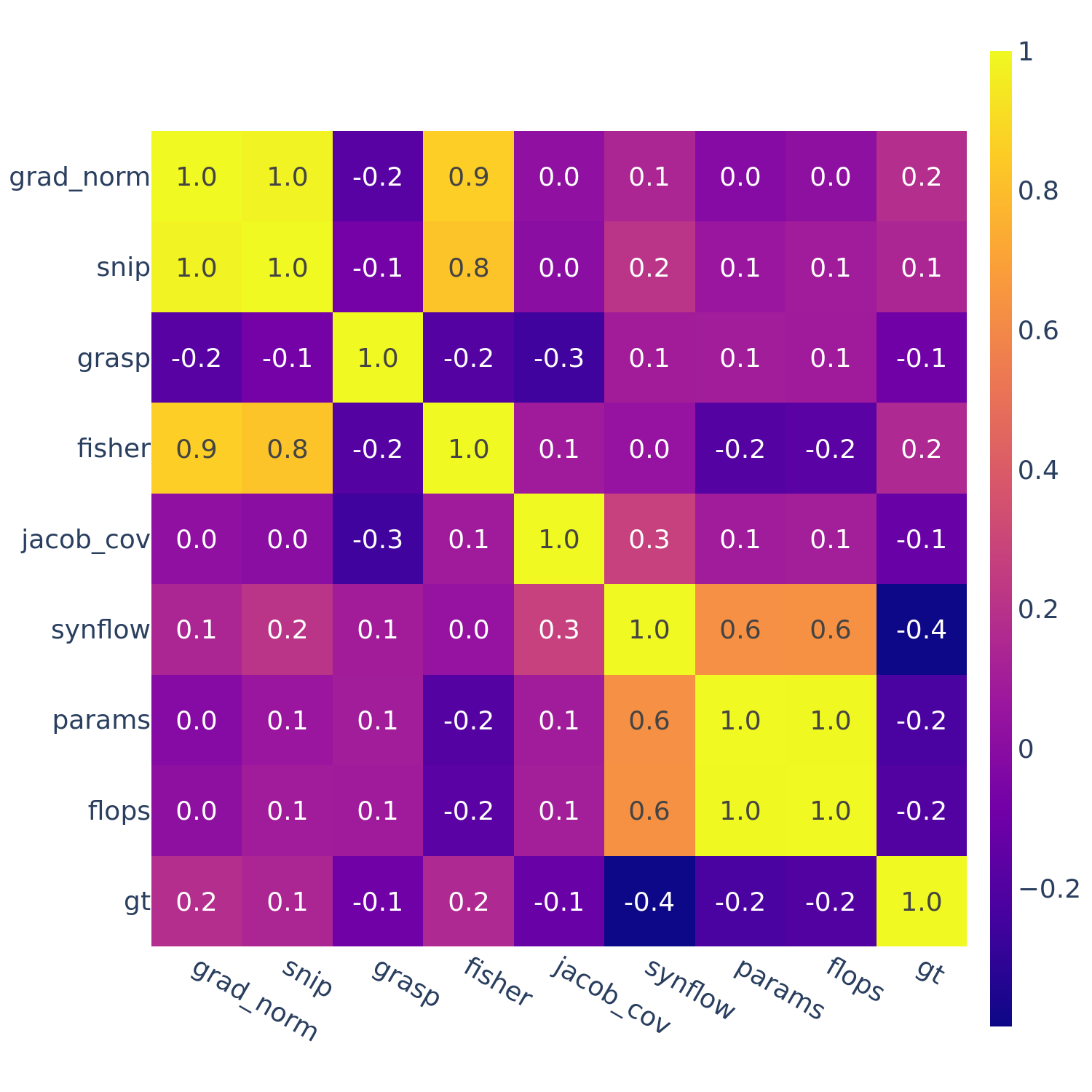

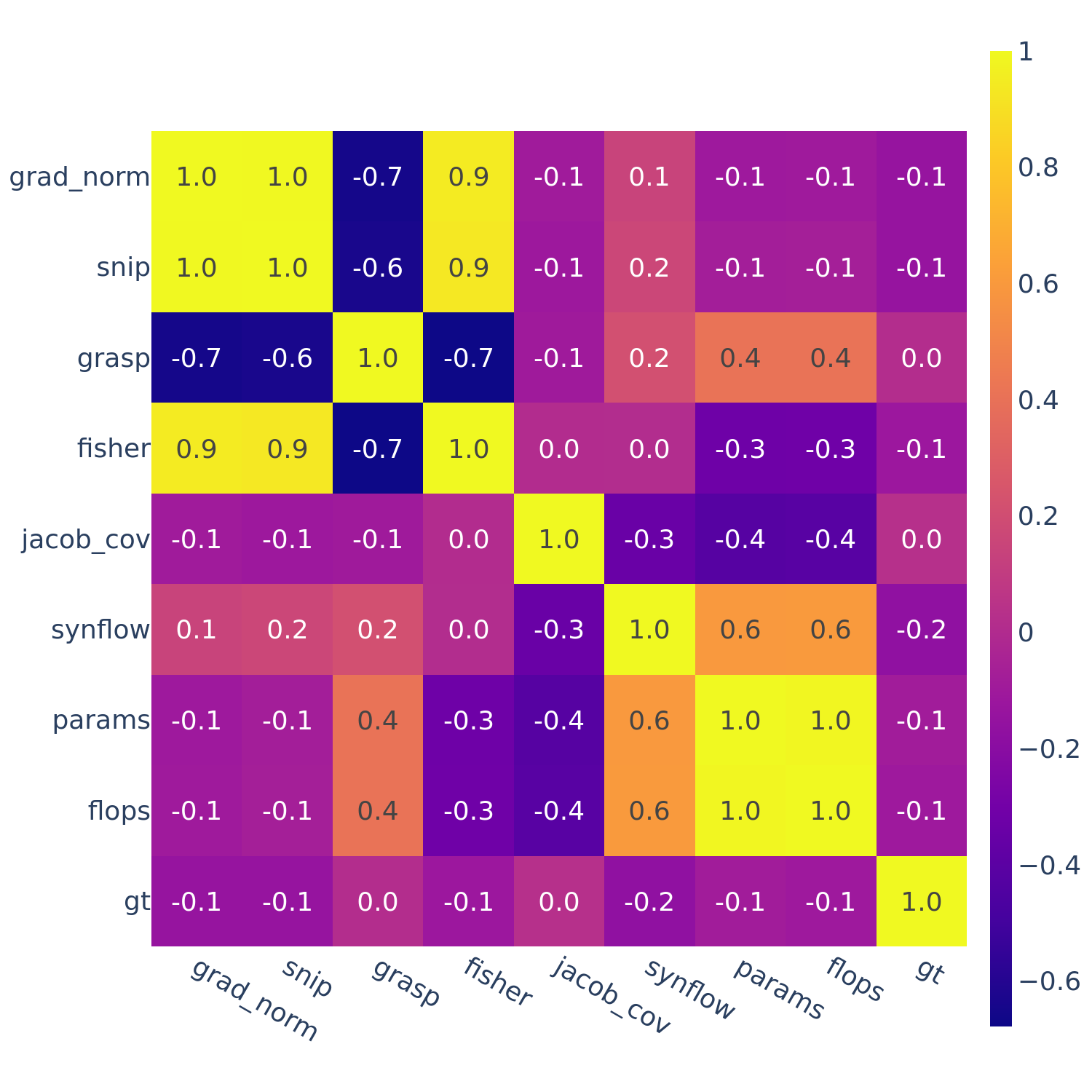

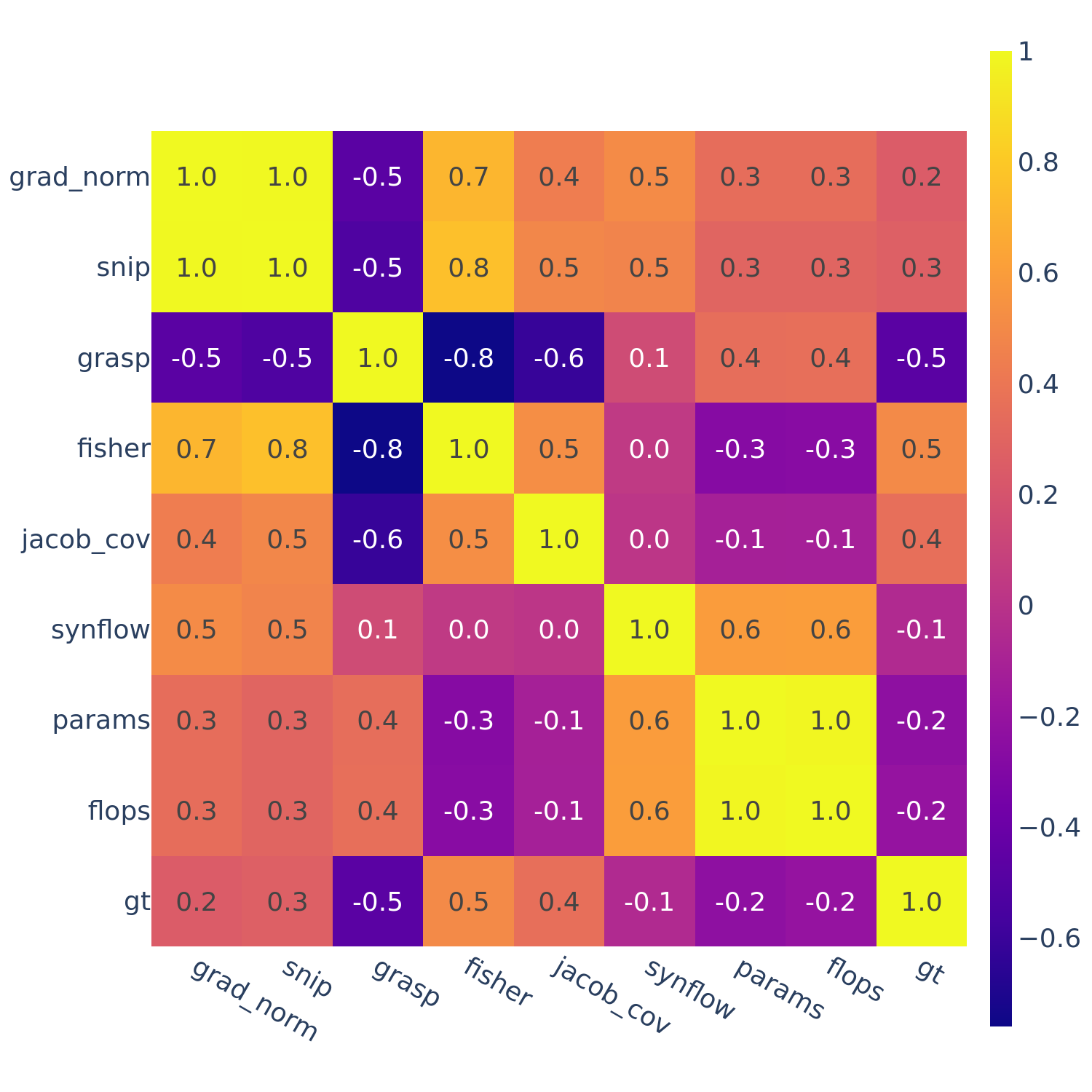

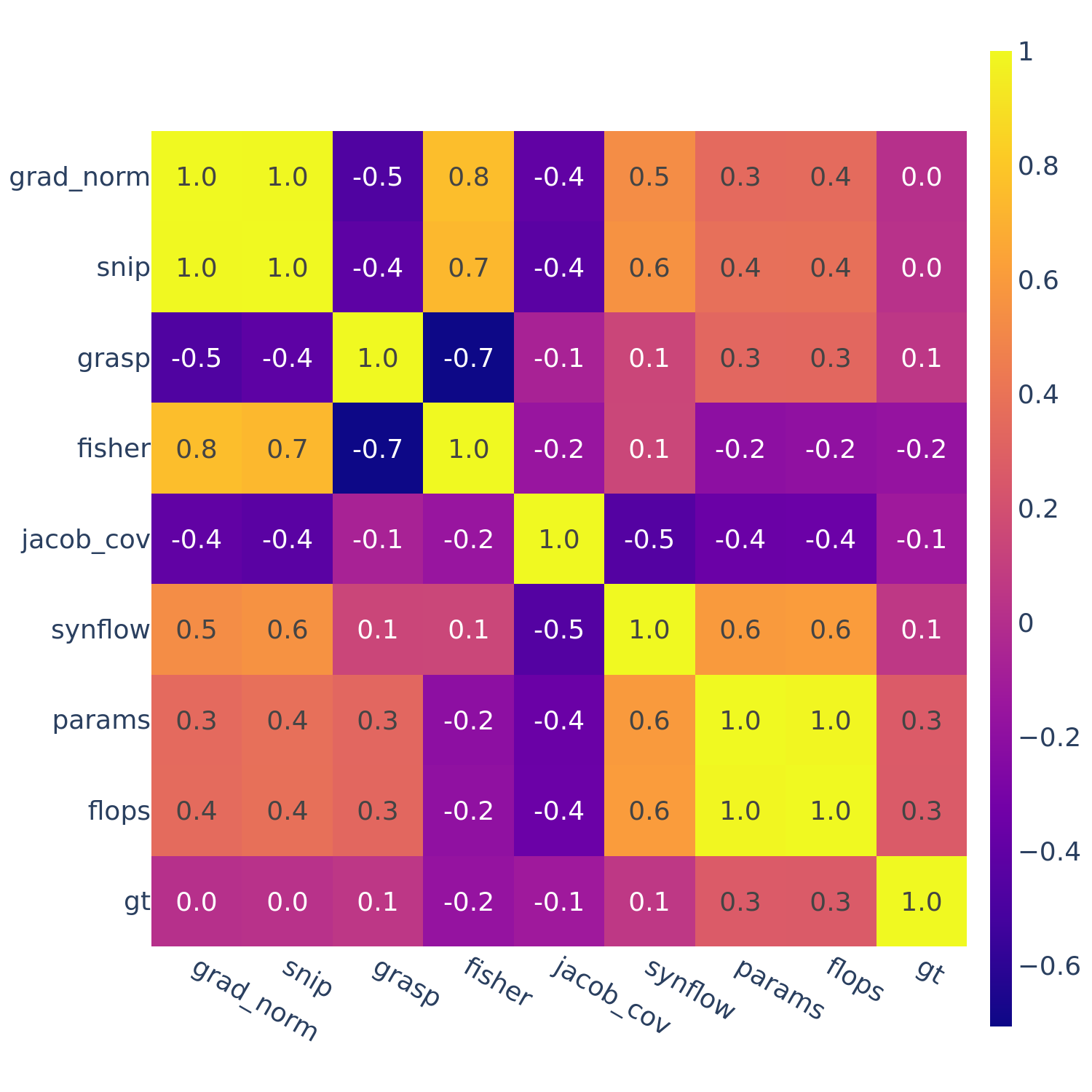

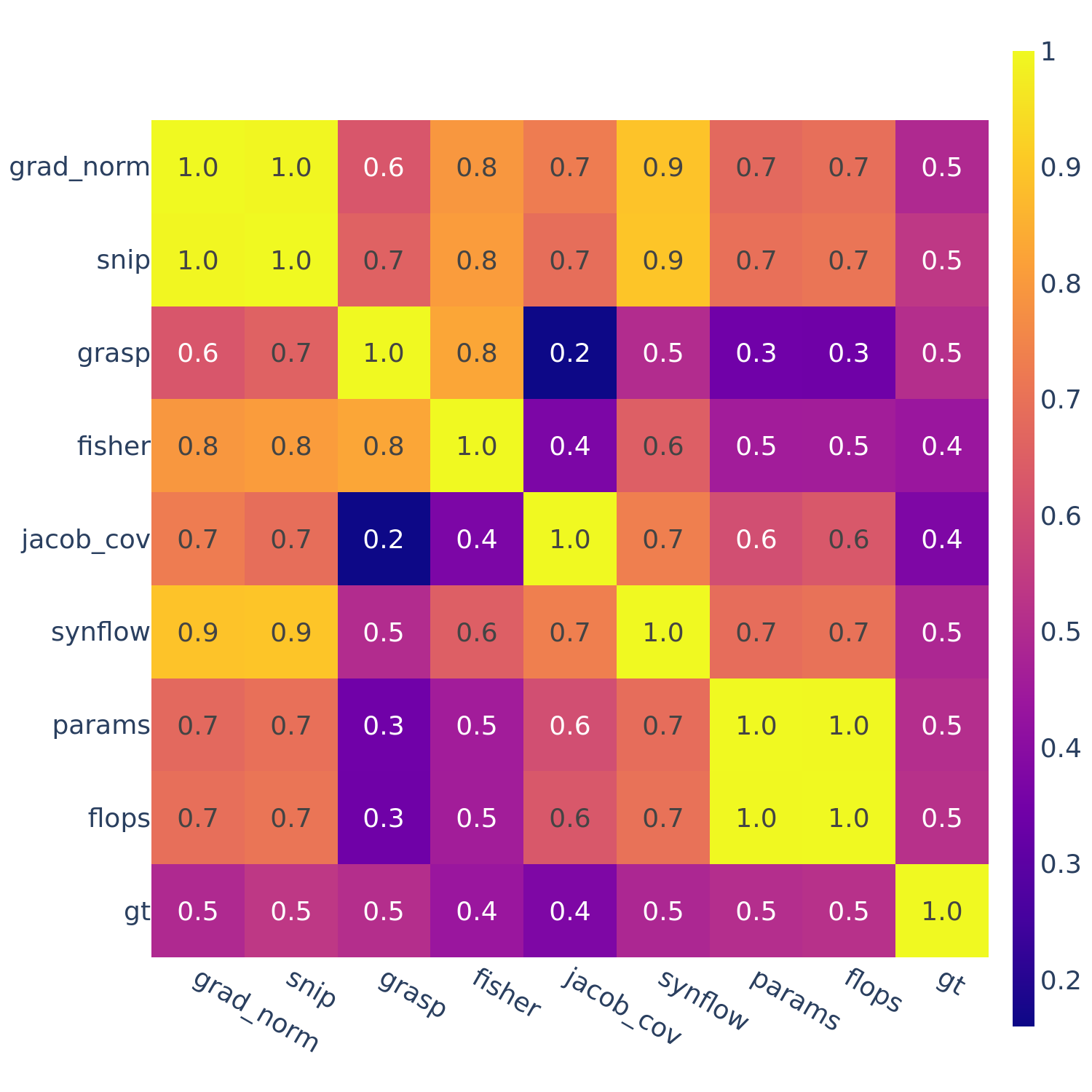

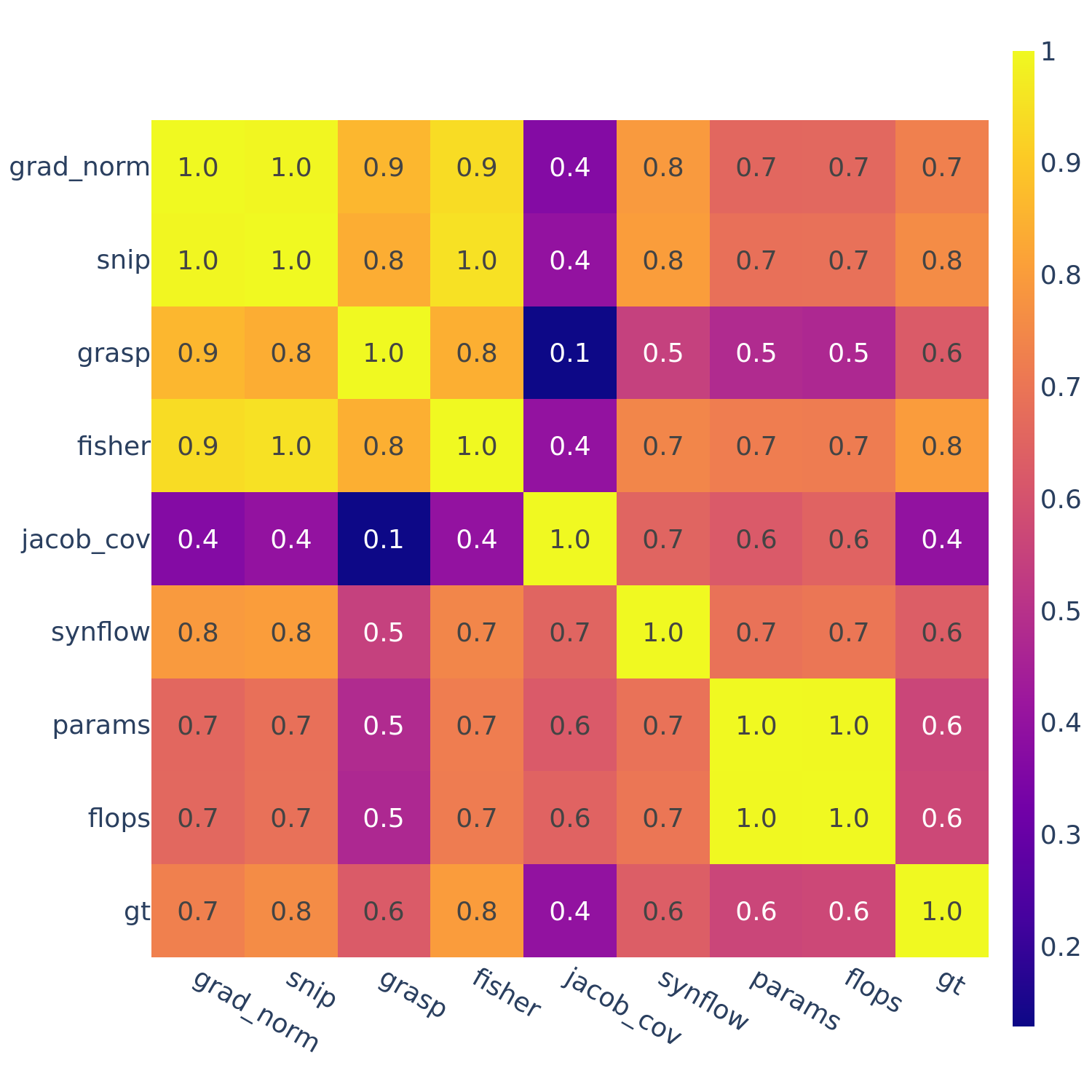

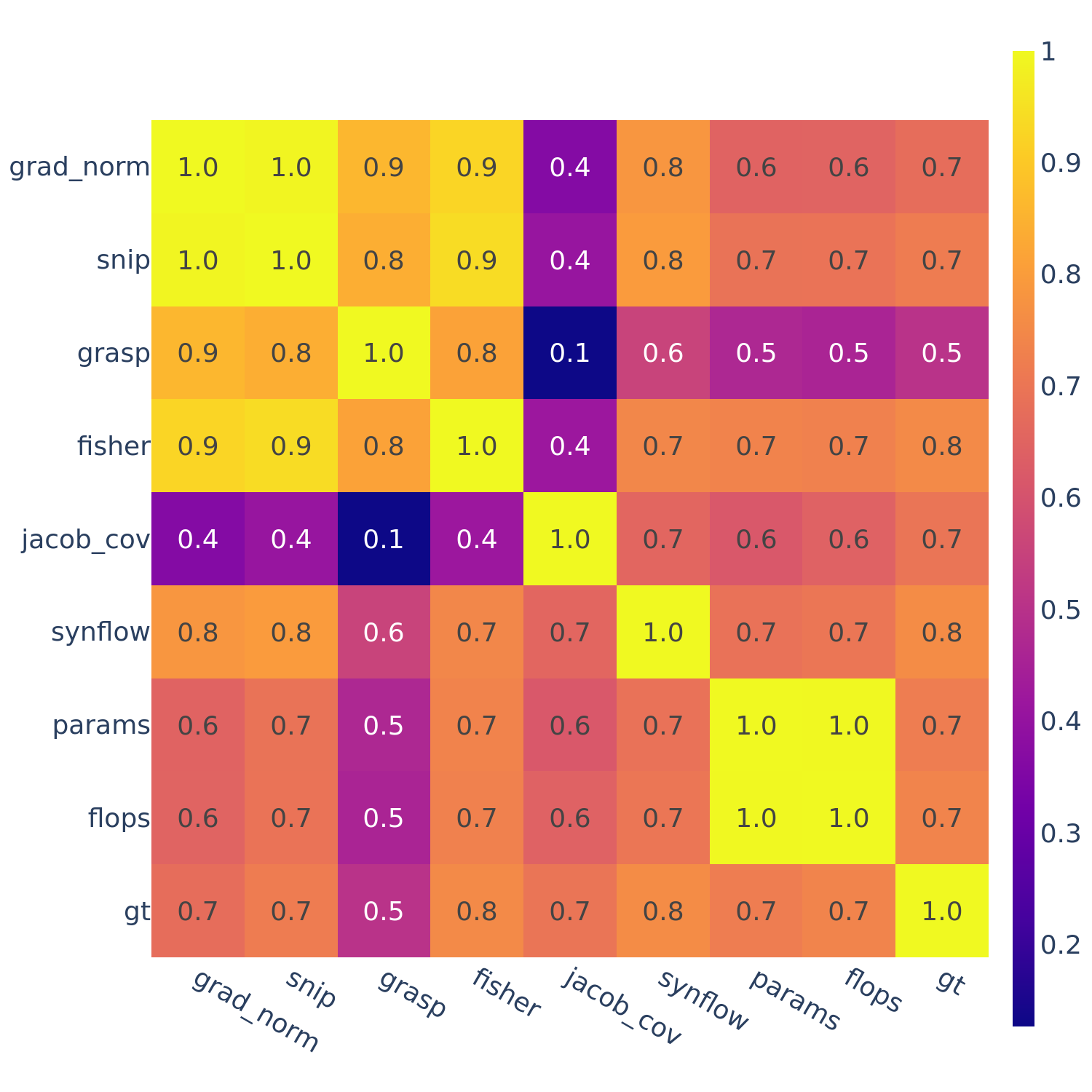

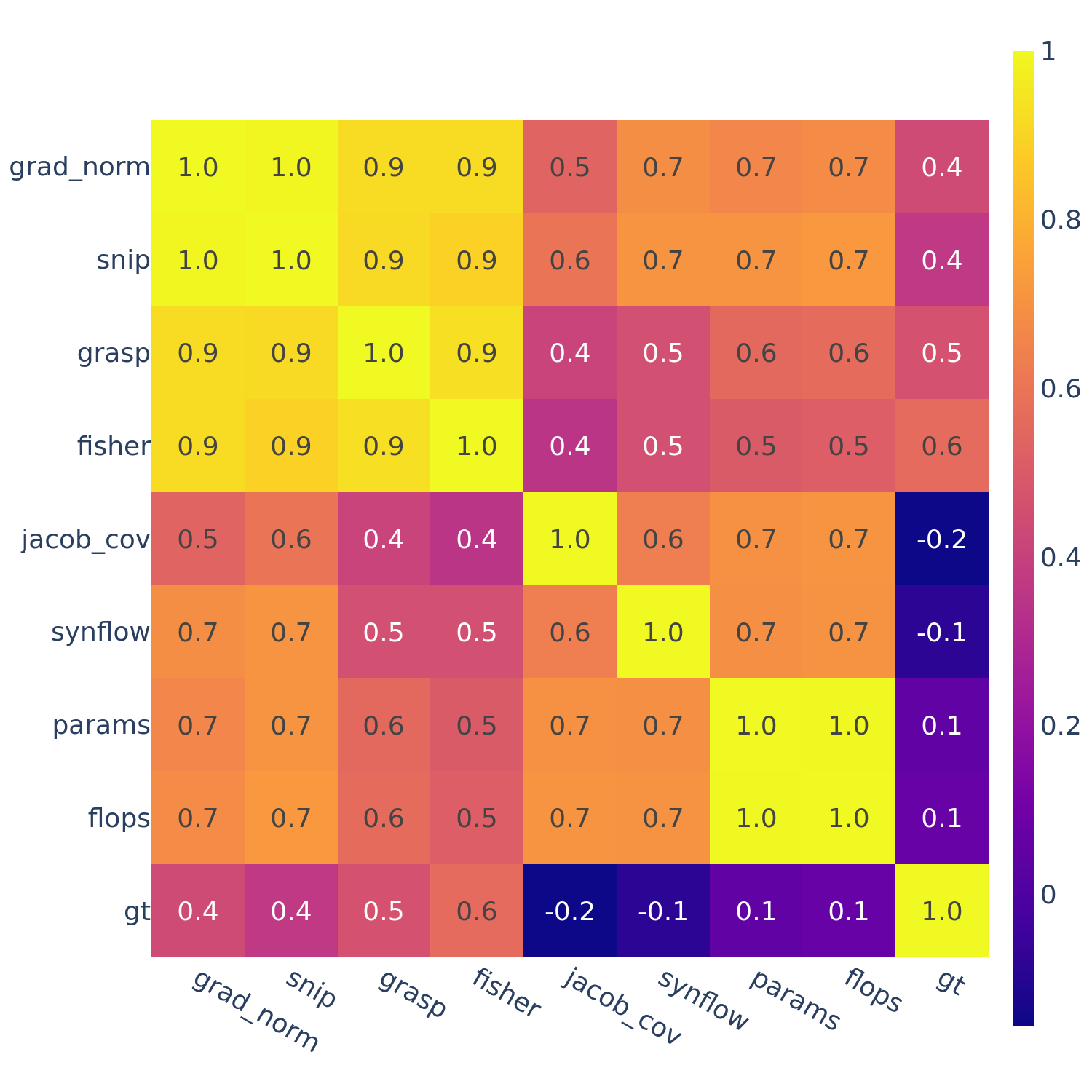

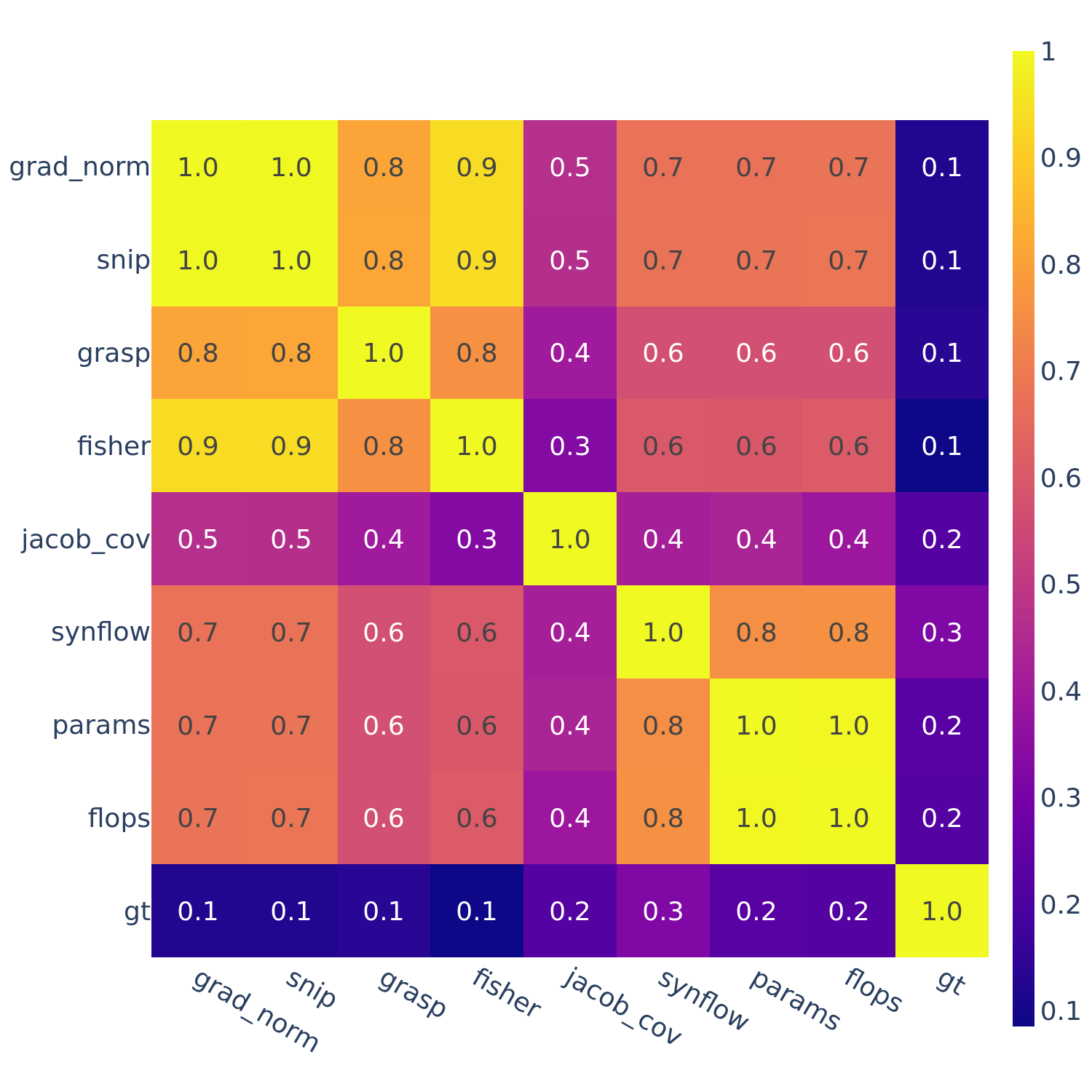

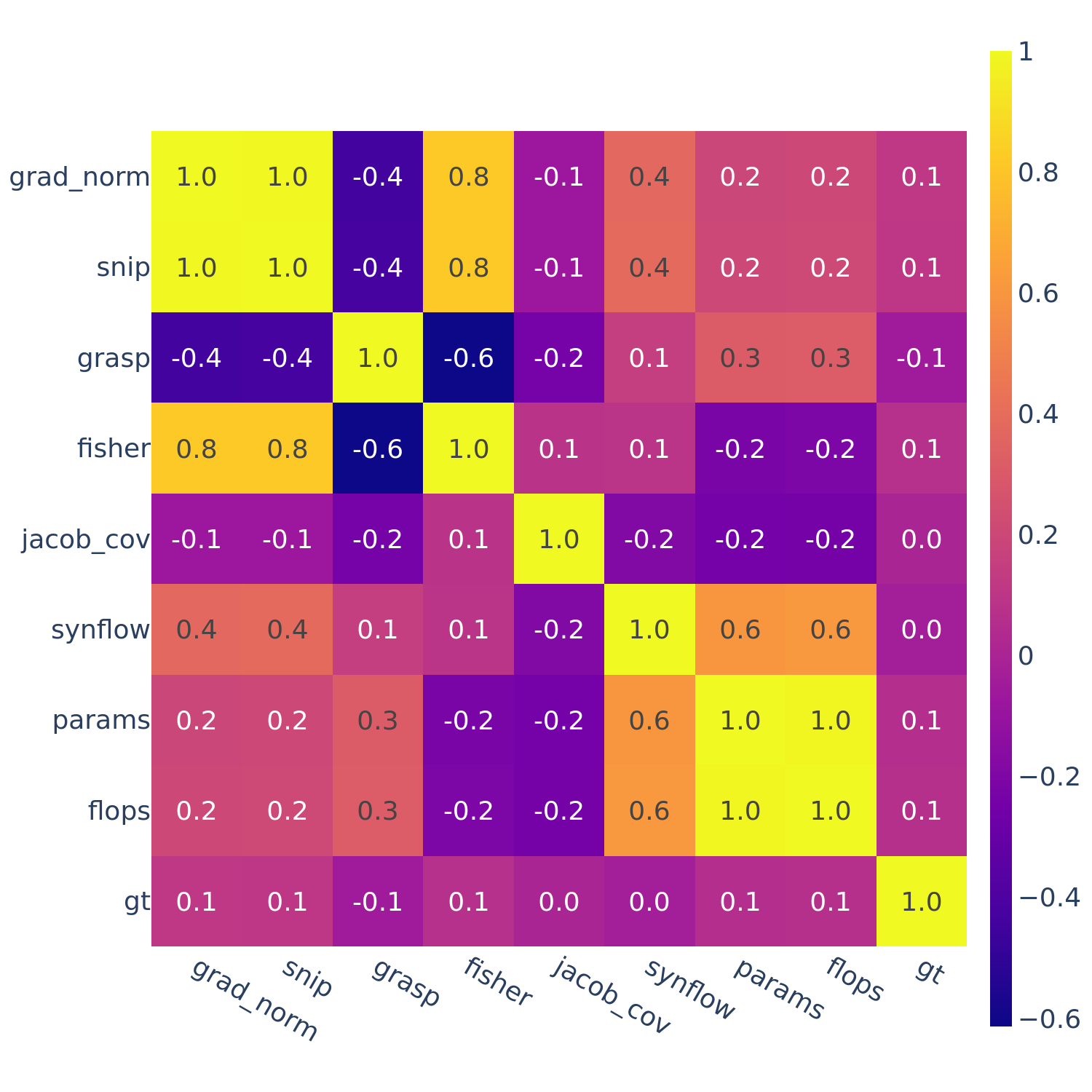

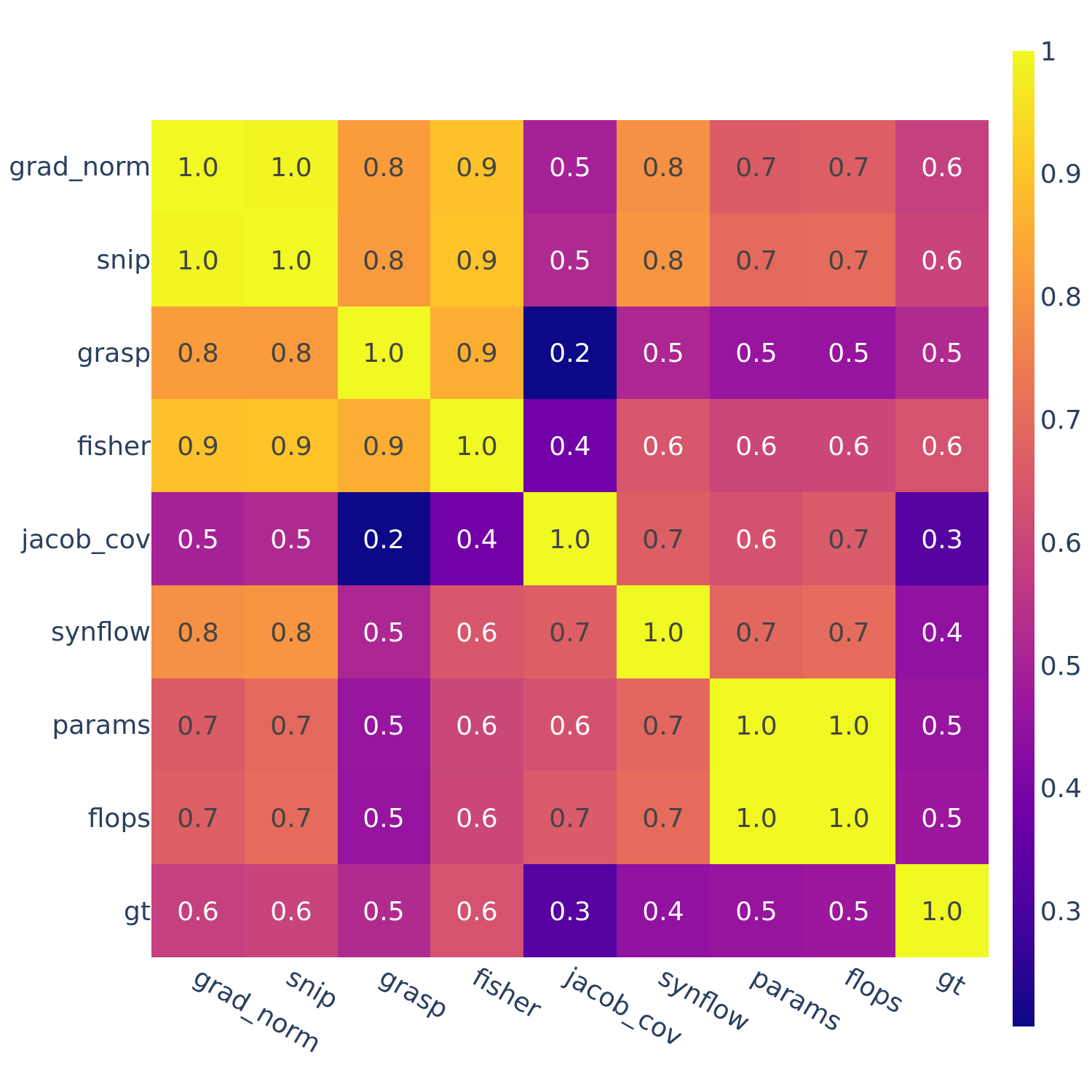

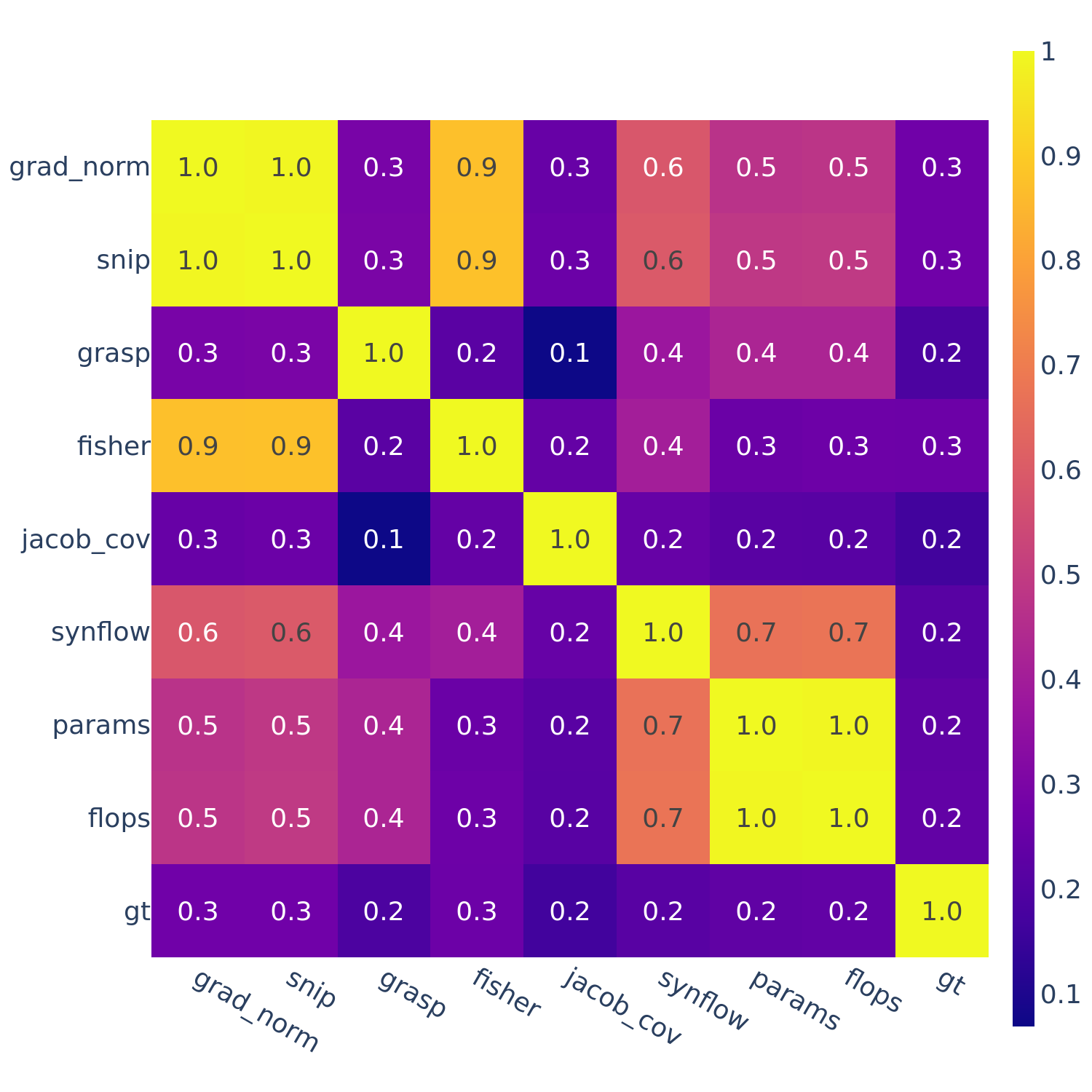

Correlations among ZC proxies

In Tables 1-3, another trend we see is that the rank correlations of some ZC proxies are correlated, such as flops and params.

This motivates the next set of figures: we compute the full correlations between all pairs of ZC proxies (as well as “gt” — ground truth performance).

Figures 3-5 give the full correlations on each of the 12 datasets, while Figure 6 gives the average correlations across each search space.

| NATS-Bench TSS CIFAR-100 |

NATS-Bench TSS Spherical CIFAR-100 |

NATS-Bench TSS Synthetic CIFAR-10 |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Figure 3: Spearman’s rank correlation among all pairs of ZC proxies on NATS-Bench Topological Search Space (TSS).

| DARTS CIFAR-100 |

DARTS Darcy Flow |

DARTS Ninapro |

DARTS Spherical CIFAR-100 |

DARTS Synthetic CIFAR-10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 4: Spearman’s rank correlation among all pairs of ZC proxies on DARTS.

| TransNAS-Bench-101 Jigsaw |

TransNAS-Bench-101 Object Classification |

TransNAS-Bench-101 Scene Classification |

TransNAS-Bench-101 Autoencoder |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Figure 5: Spearman’s rank correlation among all pairs of ZC proxies on TransNAS-Bench-101.

| NATS-Bench TSS | DARTS | TransNAS-Bench-101 | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Figure 6: Spearman’s rank correlation among all pairs of ZC proxies averaged within each search space and across all search spaces.

In Figures 3-6, we see similar trends across all search spaces and tasks.

flops and params are consistently highly correlated with one another. Furthermore, synflow is also often highly correlated with flops and params. This is consistent with recent work by Ning et al. (2021), who provided a proof that synflow’s value increases with the number of parameters in the architecture. Therefore, synflow somewhat acts as a soft parameter counter.

We also see that grad_norm, snip, and fisher are highly correlated with one another, and occasionally with grasp as well.

Relative performance of ZC Proxies

In this section, we better answer the question, which ZC proxies perform the best on average across each search space?

First, we compute the average ranking of each of the ZC proxies on each search space, and over all search spaces.

For example, if a ZC proxy was 2nd, 4th, and 6th across three datasets for a search space, then its average ranking would be 4.0.

If one of the ZC proxies consistently performed well relative to the other ZC proxies across all datasets, its average ranking would be close to 1 or 2. In Table 4, with the exception of NATS-Bench-TSS, we see that this is not the case. The top performers for NATS-Bench TSS, DARTS, and TransNAS-Bench-101 were

synflow at 1.33, params at 3.8, and fisher at 2.75, respectively. Furthermore, over all search spaces, all of the ZC proxies have an average ranking between 4.0 and 5.5. This suggests that the ZC proxies are extremely close in performance on average across all tasks.

Table 4: Average ranking of each of the ZC proxies on each search space, and over all search spaces.

fisher |

grad_norm |

grasp |

jacob_cov |

snip |

synflow |

flops |

params |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NATS-Bench TSS | 6.0 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 5.67 | 1.33 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| DARTS | 4.6 | 4.2 | 4.6 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 5.4 | 4.0 | 3.8 |

| TransNAS-Bench-101 | 2.75 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 7.5 | 3.0 | 4.5 | 4.0 | 5.25 |

| Overall | 4.33 | 4.75 | 4.67 | 5.5 | 4.33 | 4.08 | 4.0 | 4.33 |

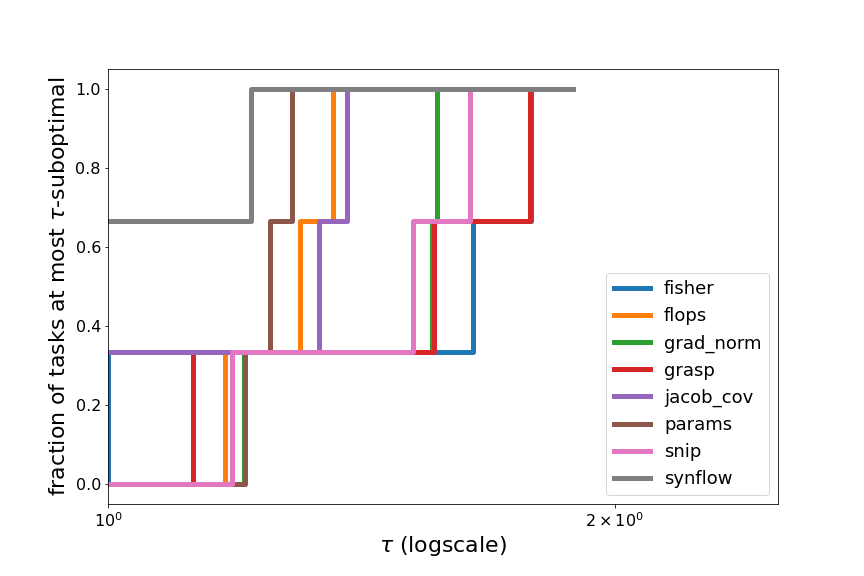

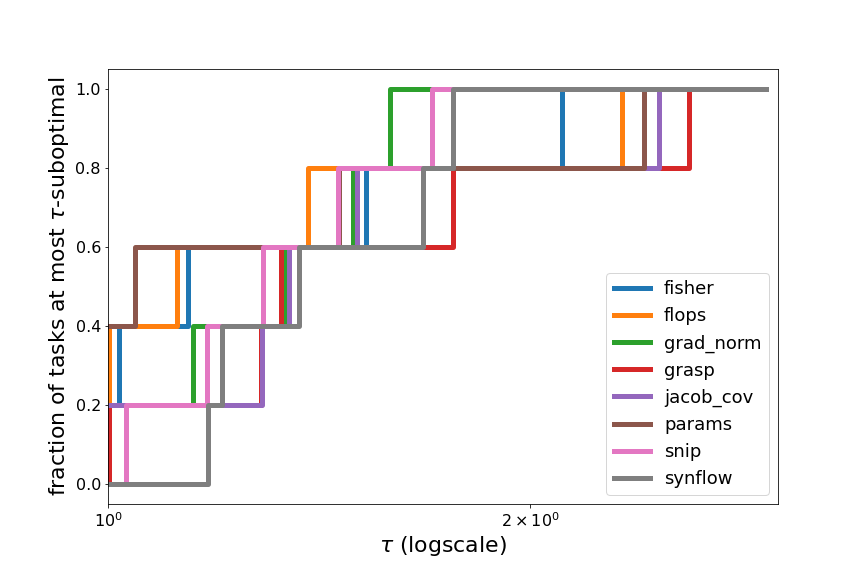

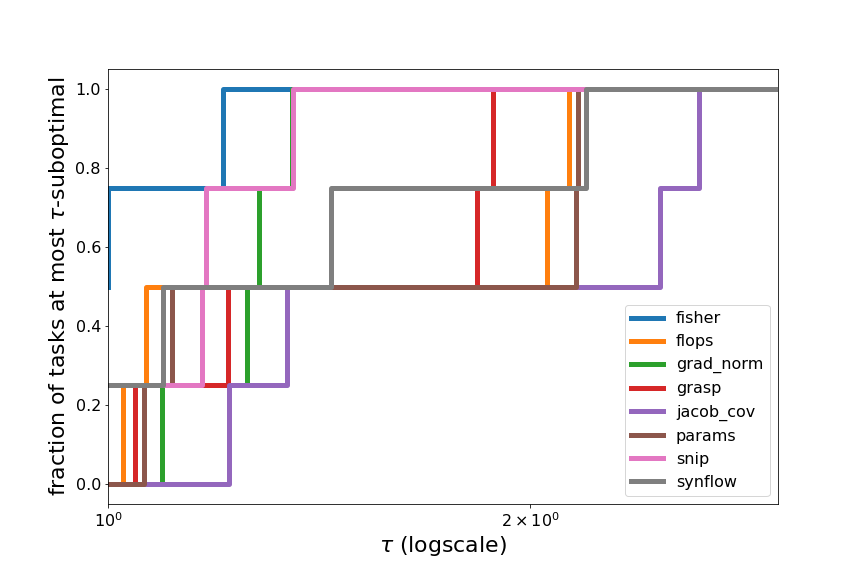

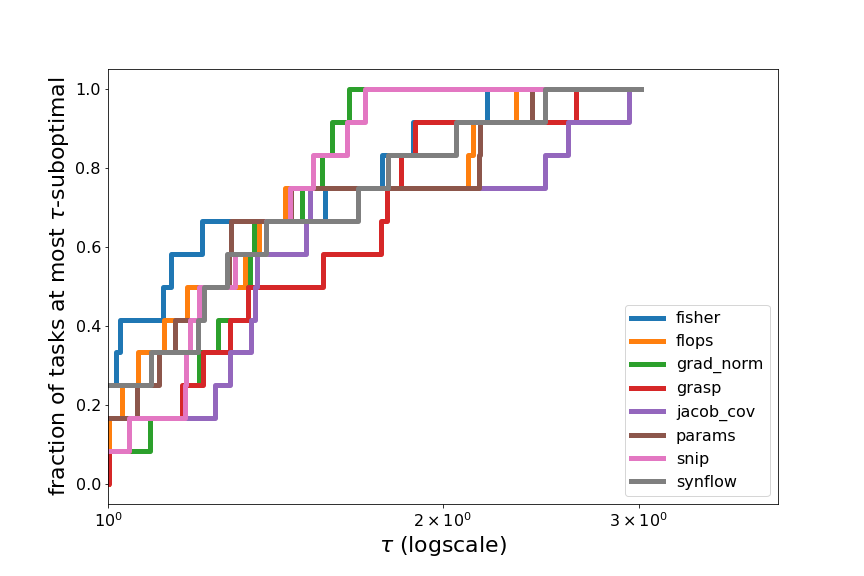

To visualize this phenomenon in a different way, we compute the relative performance profiles (Dolan et al. 2001) of the ZC proxies on each search space, and over all search spaces.

Within the Spearman value range from -1 (worst possible) to 1 (best possible), across each task, we compute how suboptimal each ZC proxy is compared to the best ZC proxy on that task, in terms of their “error” (distance of Spearman from 1). For example, on DARTS Spherical CIFAR-100, the best ZC proxy is fisher with a Spearman value of 0.4986 (error of 0.5014), and the Spearman value of snip is 0.2675 (error of 0.7325), therefore, snip is 1.46-suboptimal on DARTS Spherical CIFAR-100 (relative to the 8 ZC proxies we tested).

Across each task, we compute the fraction of tasks for which a method is at most $\tau$-suboptimal, for all $\tau$. By plotting this fraction on the y-axis, vs. $\tau$ on the x-axis, we can visualize the relative performance of the ZC proxies. If one ZC proxy were to achieve the best performance across all tasks, then its performance profile would be a horizontal line at $y=1$ (since its fraction of tasks which are 1-suboptimal is 1). In general, a ZC proxy with a line above all other lines indicates strong performance relative to the other ZC proxies. However, in Figures 7 and 8, we see that many of the plotted lines are highly overlapping, showing that the ZC proxies are relatively balanced in performance.

| NATS-Bench TSS | DARTS |

|---|---|

|

|

Figure 7: Relative performance profiles on NATS-Bench TSS and DARTS.

| TransNASBench-101 | Avg. over all search spaces and tasks |

|---|---|

|

|

Figure 8: Relative performance profiles on TransNASBench-101, and averaged over all search spaces and tasks.

Performance of ZC proxies as training progresses

Finally, we evaluate the stability of ZC proxies as training progresses. We expand on the initial results reported by Dey et al. (2021) to evaluate each ZC proxies’ Spearman rank correlation after every epoch of training on the NATS-Bench TSS search space with two different datasets: CIFAR-10 and Spherical CIFAR-100.

| Spearmans’s rank correlation vs. training epochs NATS-Bench TSS CIFAR-10 |

Spearmans’s rank correlation vs. training epochs NATS-Bench TSS Spherical CIFAR-100 |

|---|---|

|

|

Figure 9: Spearman’s rank correlation vs. training epochs on NATS-Bench TSS CIFAR-10 and Spherical CIFAR-100.

On CIFAR-10, we find that measures like snip and grad_norm gradually degrade in rank

correlation as the network trains. jacob_cov and grasp at initialization have rank correlations

of 0.69 and 0.63 respectively, but after even one epoch of training, they drastically

degrade to −0.02 and −0.41. synflow stays relatively stable.

This is not surprising given that most of the ZC proxies have

been directly applied from pruning-at-initialization literature.

Similarly, on spherical CIFAR-100, most ZC proxies degrade in performance, except jacob_cov and synflow.

From both datasets, we observe a counterintuitive property: ZC proxies are unable to take advantage of strictly increasing information. After all, as a network trains for more epochs, it only gets closer to its final fully-trained state. It would not be unreasonable to expect future ZC proxies to be able to capitalize on more information, and so we encourage designers of future ZC proxies to keep this desirable property in mind. However, we note that this property can be obtained artificially by combining the ZC proxy with a technique that already has this property. For example, there is preliminary work on combining ZC proxies with learning curve extrapolation.

Cases For and Against Zero-Cost Proxies

Based on the experiments from the previous section, and based on recent literature, we aggregate the main strengths and weaknesses of ZC proxies.

Strengths

- Speed. Although the previous section shows that ZC proxies do not always achieve a strong correlation with model performance, their speed sets ZC proxies apart from all other types of performance prediction techniques. All ZC proxies are computed with at most a forward and backward pass from a single minibatch of data. The wall-clock time depends on the size of the network and the type of data, but it typically takes five seconds or less on a GPU or CPU. We encourage the community to think of ZC proxies as cheap “weak learners”, which may be combined with other ZC proxies, or other techniques, to achieve strong performance. ZC proxies are especially useful when improving other, slower techniques at little extra cost, and/or when used as features in a prediction model, which can then choose whether or not to ignore the signal from each individual ZC proxy on a task by task basis. In the next two points, we give specific examples of this.

- Usage with model-based prediction.

There is initial work in using ZC proxies as features in model-based prediction for NAS.

Model-based prediction is a common subroutine used to guide NAS algorithms, especially in combination with Bayesian optimization (e.g. NASBOT, BANANAS, NASBOWL). At various points in time during an algorithm, when there is already a set of architectures fully evaluated, a meta-model can be trained using the architecture topology as features, and the validation accuracies as labels. This model can then be used to predict the validation accuracy of new architectures that have not yet been evaluated. White et al. (2021) showed that adding

jacob_covas an additional feature can improve performance of this model by up to 20%. Shen et al. (2021) further added ZC proxies to Bayesian optimization, showing 3-5x speedups over previous state-of-the-art methods. Additional improvements may be possible, for example, if several ZC proxies could be used as additional features instead of justjacob_cov. ZC proxies are particularly well-suited to be part of features of a model that predicts architecture performance, because it mitigates two of their downsides: the model can learn to use only the ZC proxies that are most correlated with current task, and information from multiple ZC proxies can be leveraged by the model, includingflopsandparams. - Usage with one-shot methods. There is also initial work by Xiang et al. (2021) in combining ZC proxies with one-shot methods. Specifically, this work builds off of the popular recent work on perturbation-based operation selection for differentiable NAS. Xiang et al. (2021) use ZC proxies to score operation perturbations to make decisions during the one-shot procedure. This leads to a new NAS method, Zero-Cost-PT, that can achieve up to 40x speedups compared to prior methods. Again, ZC proxies are particularly well-suited for this task, since many perturbations are encountered throughout each run of a one-shot algorithm, which must be quickly scored.

- Untapped potential.

Preliminary research shows that the best performance from ZC proxies are not when they are used individually, but when they are used in combination. For example, Abdelfattah et al. showed “vote”, the majority vote among

jacob_cov,synflow, andsnip, achieved top performance in their settings. Recent work has also shown that combiningjacob_cov,snip,synflow, andzen, as well as combining each ZC proxy withflopsandparams, leads to even better performance. Fleshing out this direction is a promising avenue for future work. Furthermore, understanding why certain ZC proxies are effective has been relatively under-studied as of now. Tackling this problem could be the key to better combining the strengths of each ZC proxy, and devising newer, better ZC proxies. Overall, ZC proxies have not yet achieved their full potential.

Weaknesses

- Unreliable performance.

In the previous section, our experiments across a diverse set of datasets and tasks showed that while ZC proxies perform well on some datasets and tasks, they do not perform well on other datasets and tasks (e.g. Gaussian data, PDE-solving, EMG signals) even when keeping the search space constant. For some tasks, the majority of ZC proxies have a negative correlation with model performance, meaning that ZC proxies would perform worse than randomly picking neural networks.

In Table 4, we even found that

flops, a simple baseline, was the ZC proxy with the best average rank over all 12 tasks we studied. Therefore, more work must be done to create ZC proxies that consistently outperformflopsandparams. There is already initial work in this direction, simply by combining ZC proxies withflopsandparams. - Unhelpful biases.

The goal of a ZC proxy is to correlate strongly with target error metrics.

However, ZC proxies have been found to have other strong preferences that may bias the search process.

For example,

synflowhas been shown both experimentally and theoretically to prefer large models by Ning et al. (2021). Furthermore, Chen et al. (2021) experimentally show thatsniphas a preference for wide channels, whilegrasphas a preference for narrow architectures. - Amdahl’s law.

In early ZC proxy research, one of the main selling points was the creation of new NAS algorithms that output an architecture in minutes. However, finding an architecture is only part of the machine learning pipeline, with discovered architectures still needing to be trained to be useful.

As a result, in practical settings, ZC proxies run into an issue akin to the one described by Amdahl’s law from parallel computing: they are optimizing only an already-fast component of the pipeline and so the overall achievable speedup is actually quite small.

For example, on the DARTS space

TE-NASreports that it takes 0.05 GPU-days to achieve a CIFAR-10 accuracy close to that of PDARTS, which takes 0.3 GPU-days; this is a six-fold improvement in search-time. This is overwhelmed by the training time of a DARTS architecture, which takes roughly 1.2 GPU-days, and thus the improvement for the full pipeline is only 1.2x. In fact, the best possible theoretical improvement according to Amdahl’s law, in the case where the ZC is truly zero-cost, is only 1.25x. However, this weakness does not apply to applications in which ZC proxies are used to improve the performance of other techniques such as model-based prediction or one-shot models, described in the “Strengths” section. - Correlation decay. Many ZC proxies, both data-independent and data-dependent, explicitly use model weights to predict an architecture’s performance. Although this has not been a target of past ZC proxy papers, ideally the predictive power of ZC proxies would increase as one trains the architecture, allowing them to be combined with early-stopping methods. However, in our experiments, we showed that in fact the performance of many proxies decreases with the number of training iterations. On the other hand, ZC proxies could be used in tandem with other techniques that do have this property, such as learning curve extrapolation. There is some preliminary work in this vein.

Conclusions and Future Directions

In this blog post, we took a deeper look at zero-cost proxies for NAS. We ran new experiments using the recent NAS-Bench-360 and TransNAS-Bench-101 benchmarks to probe the effectiveness of ZC proxies on more diverse datasets than had previously been tested in existing literature. Our main findings were the following:

- ZC proxies have differing performance profiles across tasks, and across diverse tasks, there is no single ZC proxy which performs significantly better than the others.

- ZC proxies still require further research since

flopsandparamsare very competitive baselines. - Data-agnostic ZC proxies such as

synflowhave inconsistent performance across different tasks.

In general, ZC proxies are best thought of as cheap “weak learners” which can quickly improve the performance of other techniques. Based on prior work and on our experimental observations, we view the following as particularly promising avenues for future work:

- Integrating ZC methods into one-shot and model-based methods.

- Better ways of combining ZC proxies with each other and with

flopsandparams. - Understanding why ZC proxies work well in certain situations, which can lead to the development of even better ZC proxies.

Overall, while there are currently issues with inconsistency, ZC proxies are a promising, novel direction that are sure to play a key role in future NAS techniques.

References

Taco S. Cohen, Mario Geiger, Jonas Koehler, Max Welling. Spherical CNNs. In ICLR, 2018.

Hanxiao Liu, Karen Simonyan, Yiming Yang. DARTS: Differentiable Architecture Search. In ICLR, 2019.

Barret Zoph, Quoc V. Le. Neural Architecture Search with Reinforcement Learning. In ICLR, 2017.