"Auction Learning as a Two Player Game": GANs (?) for Mechanism Design

25 Mar 2022 | mechanism-design deep-learning auctionsWe discuss a new contribution to the nascent area of deep learning for revenue-maximizing auction design, which uses a GAN-style approach in which two neural networks (one which models strategic behavior by bidders, and one which models an auctioneer) compete with each other.

Introduction

Auction design is an important topic. Goods and services of all kinds throughout the economy are sold in auctions – at least billions of dollars worth. The particular rules of those auctions are hugely important in determining “who gets what, and why” (in the words of Al Roth). The study of auction design is a very important part of the broader field of mechanism design, a research area for which four Nobel Prizes have been awarded so far.

The typical model is known as a private value auction. We assume there are some items up for sale to some bidders, and each bidder knows what each item is worth to them. That information is private (it’s called their private type, or valuation), but the typical assumption is that everybody draws their type from some prior probability distribution which is common knowledge. The auctioneer solicits bids from the bidders, who are free to strategically misreport their valuations, anticipating similar strategic behavior by the other bidders. The result is a potentially complicated Bayes-Nash equilibrium, which may be hard to even compute let alone optimize.

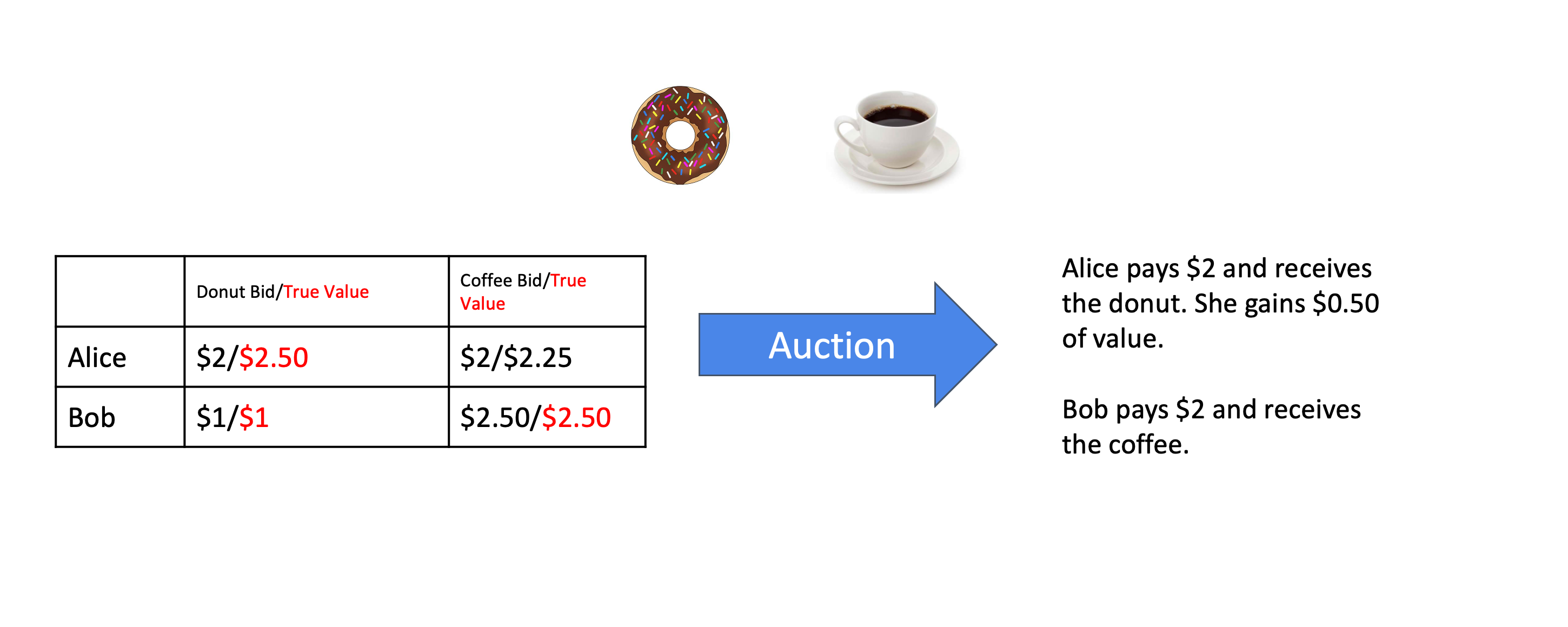

A very simple example of an auction. In this case, the allocation rule is to give the item to highest bidder, and charge exactly what they bid -- a separate first-price auction for each item. Bob is reporting truthfully, but Alice is not, and benefits because of it -- this particular auction is not strategyproof.

To cut the Gordian knot, the mechanism designer might wish to ensure that even though bidders are free to lie, there is no incentive to do so. This is known as incentive compatibility — in this post, we’ll focus on the particularly strong notion of dominant-strategy incentive compatibility (DSIC), also known as strategyproofness. A mechanism is DSIC when there is no incentive for a bidder to misreport, no matter what other bidders do. This focus on incentive compatible mechanisms is also without loss of generality due to what is known as the Revelation Principle1.

Subject to this DSIC constraint, the auction designer then wants to achieve some goal. If their goal is to maximize welfare — the total utility of all bidders — then a famous and elegant incentive-compatible mechanism known as the Vickrey-Clarke-Groves (VCG) mechanism2 can always achieve this. A natural goal for an auctioneer, though, is to instead maximize revenue.

Revenue maximization for selling a single item was completely settled by Myerson in a famous and excellent paper. Beyond this, finding revenue-maximizing auctions has proven very challenging. There are some results in limited settings (particularly for single-agents and for some binary valuation distributions), but a general theory seems to be totally out of reach. To make this concrete, consider selling two items to two agents, where the valuations are i.i.d uniform on the unit interval. This case seems like it should be trivial, but the optimal mechanism is not known even after decades of research by some very smart people.

This lack of theoretical progress motivates a different approach: automated mechanism design. Given knowledge of the distribution (in the form of samples), can we somehow learn a good — hopefully optimal — mechanism? There’s a lot of work in theory and in practice in this direction. In this blog post, we’ll be focusing on the nascent area of differentiable economics — the use of rich, differentiable function approximators to represent classes of mechanisms, which can be trained using gradient-based methods to achieve desired goals.

In particular, we’ll be focusing on “Auction Learning as a Two-Player Game”, which appeared at ICLR . This paper builds on previous work that represents allocation and payment rules as feedforward neural networks. It differs by also modeling bidder’s strategic behavior as a neural network. The resulting training algorithm strongly resembles a GAN.

Formulation

The Mechanism Design Setting

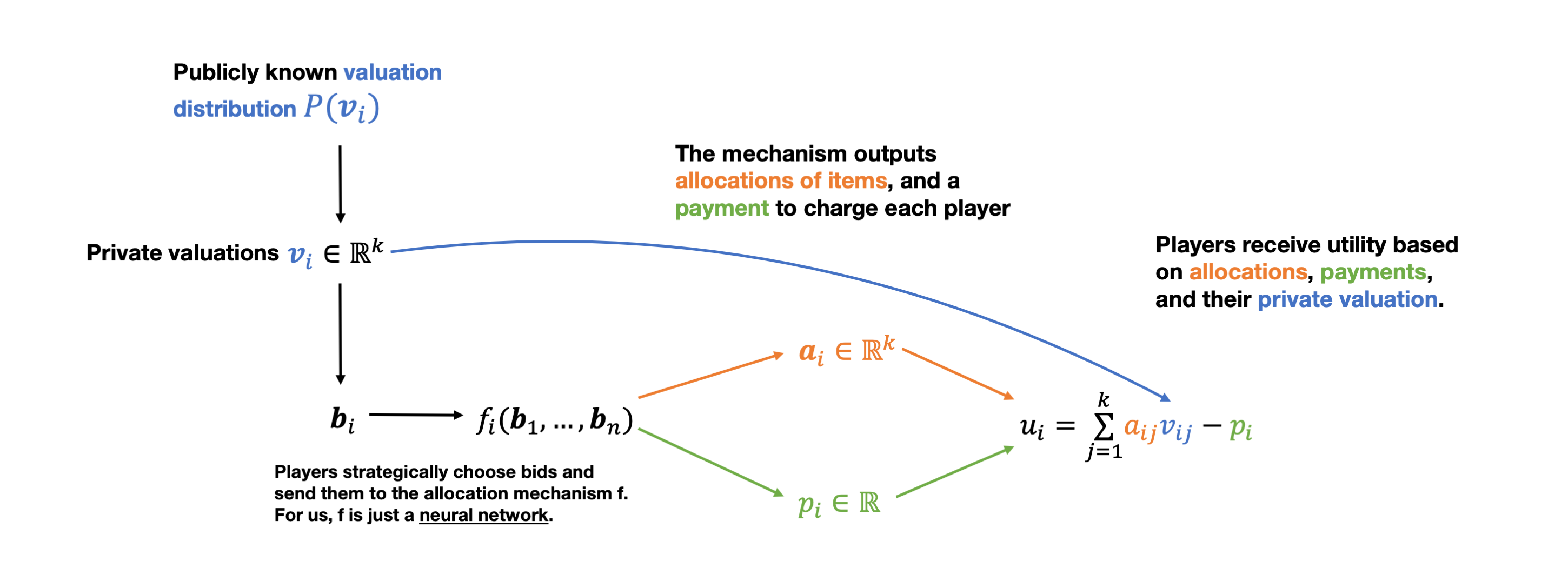

This schematic shows the process of a multi-agent, multi-item auction with additive valuations.

Let’s make things concrete. Suppose there’s $n$ agents buying $m$ items. Each agent’s valuation vector is just a vector $v \in \mathbb{R}^m$ specifying how much they value each of the items. We will sometimes refer to a bid $b \in \mathbb{R}^m$, which is just a non-truthful report of a valuation vector.

Then the auction mechanism consists of a pair of functions $(a, p)$.

- $a: \mathbb{R}^{nm} \rightarrow [0,1]^{nm}$ is the allocation rule – it takes in all bids from all $n$ agents, and outputs an allocation specifying which agent gets which item. We allow these allocations to be fractional – you can interpret this as either offering goods that are divisible, or offering “lottery” allocations.

- $p: \mathbb{R}^{nm} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^n$ is the payment rule – it simply specifies how much to charge each player.

We assume that utilities take the form $u_i = \langle v, a_i \rangle - p_i$. Then we can formalize the strategyproofness constraint by defining the quantity known as regret:

\[\text{rgt}_i(v) = \max_{b_i} u_i(b_i, v_{-i}) - u_i(v_i, v_{-i})\]That is, regret is the difference in utility between telling the truth by reporting $v_i$, and the best possible misreport $b_i$. Here, we’ve defined regret for a particular set of valuations, and for a particular player. When $\text{rgt}_i(v)$ is 0 for every player $i$ and for every possible valuation profile $v$, the mechanism is dominant-strategy incentive compatible.

Let $\mathcal{M}$ be the set of feasible mechanisms – those where regret is 0, where allocations are always feasible, and where individual rationality (IR) is respected. IR here means, that any agent will receive non-negative utility from participating in the mechanism, i.e. never pay more for a bundle of items than their valuation of that bundle. The mechanism designer’s problem is then:

\[\max_{(a,p) \in \mathcal{M}} \mathbb{E}_v\left[\sum_i p_i(v)\right]\]Here, all the mechanism designer cares about directly is maximizing their revenue (the sum of all agent payments). However, because of the IR and DSIC constraints, maximizing payment also requires carefully choosing $a$ along with $p$.

Mechanism Design As Learning

To anyone with a machine learning background, the optimization problem above is obviously a learning problem – we’re choosing a function from some class in order to maximize an expected value over a prior distribution. This connection is not new. Treating mechanism design as a learning problem has been worked out very thoroughly in the computer science literature over the past two decades or so, with a particular focus on sample complexity, generalization, and other learning-theoretic concerns.

What is relatively new is the use of applied techniques from deep learning. The idea is that $a$ and $p$ are just functions, and modern deep learning has given us rich, easy-to-use classes of function approximators – so why not apply those to auction design?

RegretNet

A major contribution in this direction was the paper “Optimal Auctions Through Deep Learning”. The idea is that $a$ and $p$ are ultimately just functions which can be directly approximated by feedforward neural networks. We assume access to a lot of sampled valuations, and just maximize revenue via gradient ascent.

The challenge is that we also want to satisfy our constraints — we want to ensure that $(a, p) \in \mathcal{M}$. Can we design the architecture to make sure this always holds? In some special cases (discussed in the paper) the answer is yes. In general, though, this is quite a challenging problem. In particular, it’s possible to architecturally enforce that allocations be valid, and that IR be respected – most challenging is ensuring DSIC.

The RegretNet approach is to include an augmented Lagrangian term in the loss function to enforce the DSIC constraint.

That is:

\[\min_{(a,p)} \max_{\lambda>0} - \sum_i p_i(v) + \sum_i \lambda_i \text{rgt}_i(v) + \frac{\rho}{2}\left(\sum_i \text{rgt}_i^2\right)\]The regret term, which is a maximization, can’t be easily computed directly — this would require globally optimizing over all possible bids. Instead, it is approximated by taking a few steps of gradient ascent on the network inputs. This works almost exactly like computing an adversarial example, and the result is that (as noted in one early version of Duetting et al.) the RegretNet training loop seems quite a bit like adversarial training.

There are some limitations to this approach. First, re-computing the misreports at each step seems quite inefficient (RegretNet does at least use the previous iteration’s results for a warm start). Second, the schedule for adjusting the Lagrange multipliers is a fairly finicky process – it’s a lot of extra hyperparameters to tune that can have a huge effect on final performance.

However, it can be made to work. In addition to correctly finding optimal mechanisms in cases where they are known, RegretNet achieved convincing SotA results in settings outside the reach of previous automated mechanism design. Moreover, there has been a myriad of followup works, many of which use the same basic RegretNet training approach (including learning fair auctions, facility location, symmetric auctions and many more).

The GAN-like approach of “Auction Learning As a Two-Player Game”

We’ve pointed out that the RegretNet training loop looks quite a bit like adversarial training (albeit, as we’ll see, not exactly zero-sum), so what about using another adversarial learning technique, namely GANs?

“Auction Learning as a Two-Player Game” takes this approach. The allocation and payment networks look roughly the same. The misreports, however, are computed by a neural network, which learns to map truthful bids to regret-maximizing lies. An additional contribution is a new loss function, motivated by results from auction theory, which avoids the finicky use of Lagrange multipliers, making hyperparameter tuning much easier and more reliable. This new approach is called “ALGNet”.

Recap on GANs

For readers not familiar with Generative Adversarial Networks, we recommend the following blog post. GANs are most typically used for generating fake images that look similar to images from a real-world dataset. The idea is that there are two competing neural networks: a generator which transforms a source of random noise into a fake image, and a discriminator, which tries to tell apart real and fake images. The generator tries to minimize discriminator accuracy, while the discriminator tries to maximize it – the result is a saddle-point problem. As the discriminator improves, the generator has to create more and more realistic images in order to continue fooling it.

Where are GANs and ALGNet similar and where do they differ?

With both GANs and ALGNet, we have two architectures based on adversarial learning between two players. In a GAN, these are the Generator (who observes some randomly-sampled features and transforms it into a fake image) and the Discriminator (who tries to predict whether an image is fake or real); in ALGNet, these are the Auctioneer (who chooses allocations and payments) and the Misreporter (who tries to come up with high-regret misreports).

In both, one player tries to come up with a game, and one player tries to cheat well at it.

The analogy between the players is not clear cut, though, and the Auctioneer and Misreporter each have features of both Generator and Discriminator. Both are like the generator: the Misreporter tries to generate misreports that will fool the auctioneer; at the same time, the Auctioneer observes randomly-sampled bids and tries to output allocations/payments that are hard for the misreporter to manipulate. But they both use the outputs of the other player to quantify their success, as the Discriminator would in a GAN.

Another key difference is that a standard GAN is zero-sum, as in a pure saddle-point problem. For example, in a visual GAN, both players’ loss is just whether fake images deceive the Discriminator, so that the Discriminator’s loss is exactly the Generator’s gain.

Here, we can see the loss from deception in a traditional GAN being roughly equivalent to regret of the auctions in the ALGNet. Both the Auctioneer and Misreporter care about it, and one player’s loss is the other’s gain. In a loose analogy, it quantifies the degree to which misreports are not properly being recognized as such, or in other words, how close to DSIC the auctions are.

What makes the ALGNet non-zero-sum and not a clean saddle-point problem is the following: apart from regret, we also have the revenue of the auctions entering the loss term for the Auctioneer player only, turning it into a general sum game. Two-player zero-sum games are usually nicer to deal with; general-sum games are much less pleasant. However, the ALGNet approach still works quite well in practice, as we’ll see below.

Why is the GAN approach more efficient?

In the RegretNet approach, misreports are in principle recomputed from scratch every time the auction parameters and Lagrangian multipliers get updated. This essentially means there are multiple costly gradient steps in an additional inner loop during training, and that no information is shared between any of the bids. (Actually, RegretNet is at least able to use the previous misreports to “warm start”, but the computational cost is still significant.)

However, it is reasonable to assume that the structure of the misreports can be learned by a neural network. Although the mapping from valuations to optimal misreports may be complex, we do expect that similar valuations should for the most part have similar misreports, so that some amount of generalization across bids is possible. Using this approach, it is not necessary to recompute misreports every time, and the number of parameters in the neural network need not grow with the size of the dataset.

On the other hand, the authors find that many updates of the Misreporter are required for every step the Generator, so there is still in effect a costly inner loop.

By resetting the parameters of the misreporter periodically during training, we can try to prevent getting stuck in local optima, but the reset intervals are independent of parameter updates for the Auctioneer.

Needing to tune fewer hyperparameters also has positive effects on the complexity of ALGNet training.

Trading Off Revenue And Regret

$\epsilon$-Incentive Compatibility

Our goal is to maximize revenue, subject to the constraint of having 0 regret. Neither RegretNet nor ALGNet can exactly achieve this second goal – they always have some very small but nonzero regret. Thus, they’re really $\epsilon$-incentive compatible, not actually DSIC.

On the other hand, $\epsilon$ is extremely small in practice, and known optimal DSIC mechanisms are approximately recovered, so we have reason to believe that we are actually finding approximately optimal auctions as desired.

A New Loss Function: $\sqrt{\text{Profit}} - \sqrt{\text{Regret}}$

However, the presence of nonzero regret poses another problem. We now have two criteria for performance: making revenue large, and making regret small. We can simply measure and report both, but it’s not clear how to trade off between these: how much revenue should we give up to decrease regret a little further? Implicitly, RegretNet regulates this tradeoff by the strength of the Lagrange multiplier, which is constantly shifting during training. The need to update this Lagrange multiplier is what introduces the finicky hyperparameters that make tuning and training RegretNet relatively brittle.

The authors of ALGNet present a different technique motivated by auction theory. There is a construction whereby an auction with total revenue $P$ and total regret $R$ can be converted into an auction with revenue $P’ = (\sqrt{P} - \sqrt{R})^2$, which has regret $R’ = 0$ (i.e. is strategyproof). This construction only works in the single-agent case, or under a weaker notion of incentive compatibility (Bayes-Nash Incentive Compatibility), but the authors conjecture that it can be extended to the multi-agent case.

If the conjecture holds, then every non-DSIC auction can be converted into a “canonical” DSIC auction; applying this transformation to two auctions is a good way to compare performance between them. Whether or not that conjecture holds, the authors argue convincingly that it is at least a good heuristic for trading off regret and revenue.

Thus, the authors just use $-(\sqrt{P} - \sqrt{R})$ as their training objective. This has a direct practical benefit in training: there are no hyperparameters and the loss function doesn’t change over time. And (perhaps with only a tiny amount of hand-waving) it provides a fair way to compare different trained auctions.

(Actually, they use $-(\sqrt{P} - \sqrt{R}) + R$, as in practice it more reliably trains to near-zero-regret mechanisms. But this still doesn’t have any hyperparameters.)

Empirical Successes

Lack of Hyperparameter Tuning

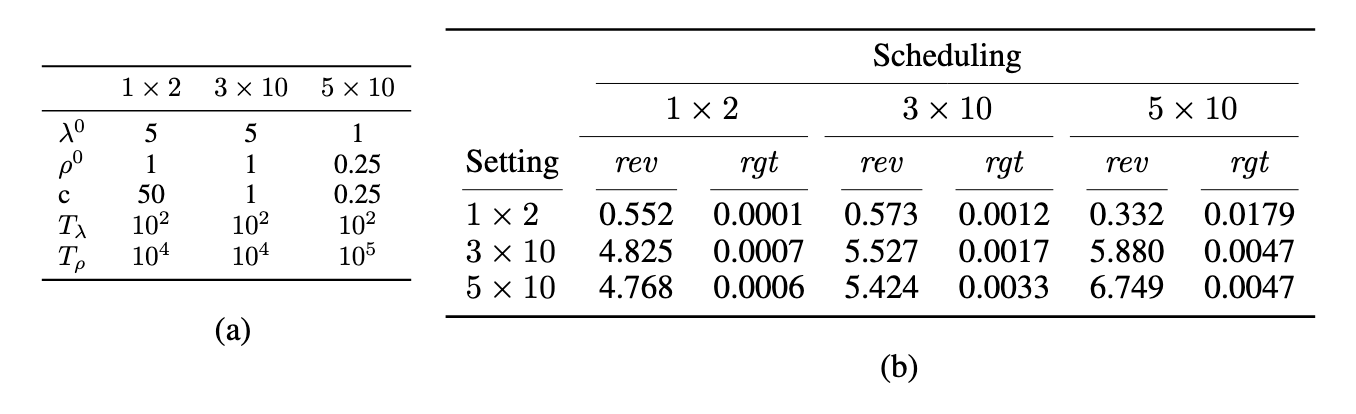

Here, we reproduce Table 1 from the paper, which shows that the hyperparameters associated with the augmented Lagrangian weights are quite brittle. Section a) shows the best hyperparameters for 3 auction types: 1 agent 2 items, 3 agents 10 items, and 5 agents 10 items. Section b) shows performance of each hyperparameter setting on its own as well as the other auction types.

A major advantage of ALGNet over previous approaches is that there are simply fewer hyperparameters. While RegretNet can perform well after hyperparameter tuning, those hyperparameters are relatively brittle. Consider Table 1 from the paper (reproduced here), which looks at the effect of the Lagrangian-related hyperparameters specifically. The authors take 3 different types of auctions with the best hyperparameters for each type, and compare performance on each pair. The result of training on the wrong hyperparameters is a quite severe degradation in performance. A core result in auction theory is that adding an additional customer should always bring in more revenue, so having less revenue for 5 bidders than 3 is quite bad!

By contrast, the ALGNet approach avoids these hyperparameters entirely, and is indeed much less brittle. Its performance on each of these settings is comparable to RegretNet’s performance with the best hyperparameters.

Good Performance

In terms of overall performance, ALGNet competes with or exceeds RegretNet. In particular, for very large settings with 3 or 5 bidders and 10 items, deep-learning-based approaches are the only automated mechanism design techniques that really work at all. In these settings, ALGNet achieves competitive revenue and similarly small regret, but (as mentioned) requiring much less hyperparameter tuning. We also note that ALGNet adapts more quickly than RegretNet in non-stationary cases (where the underlying valuation distribution shifts over time).

Limitations

But what about theoretical guarantees! And isn’t all that uninterpretable?

Many people, especially those less familiar with deep learning, might be wondering what can be guaranteed about these algorithms. Will they always converge to a locally optimal, or even globally optimal, auction? Can anything else be said?

The theory of GANs is pretty well-studied. To give a random sampling of some results, in general, there’s no guarantee that a Nash equilibrium exists; on the other hand, depending on assumptions, equilibria might exist and SGD can be shown to converge in at least some special cases. Convergence proofs for global optima exist in settings with sufficient overparametrization when Gradient Descent-Ascent is used, but even such convergence guarantees have little practical relevance.

Also, in the case of ALGNet, we are dealing with a general sum game, an even more difficult setting. So we don’t have or expect many formal convergence guarantees for these algorithms. In practice we can check empirically that the resulting mechanisms do in fact have the desired properties, and this is the best choice.

Another argument often made against neural network approaches is limited interpretability and explainability: this is an active area of research in machine learning. This poses a problem for deep-learning-based auctions as well – there’s something unsatisfying about telling a bidder “the rules of the auction consist of this opaque set of neural network weights, we promise they’re strategyproof, good luck”.

Some neural architectures specialized to the single-agent setting – RochetNet and MenuNet – are already quite interpretable; making deep architectures for multi-agent problems that are also interpretable would be interesting. There is at least one approach in this direction (though with more limited expressive capacity than ALGNet or RegretNet). We see some potential in applications of techniques from interpretability research in general. Finding out exactly how overparameterized a deep learning setup needs to be might also lead to smaller models for auctions and better understanding of their convergence guarantees, possibly improving interpretability.

Finally, one limitation of these approaches may be obvious to mechanism designers – the strategyproofness is only approximate, and can only be estimated, not measured precisely. Some work exists to mitigate this second limitation by precisely certifying the level of regret. As for designing exactly-strategyproof mechanisms, this is only possible in the single-agent case (RochetNet and MenuNet again), because strategyproof mechanisms are quite well-understood in this case – their allocation rules are the gradients of convex utility functions. Strategyproof multi-agent multi-item auctions are not so well understood, and exactly-strategyproof architectures might first require advances in auction theory.

In conclusion: since more complex auction settings could so far not be solved using techniques for which rich theory exists, we think the tradeoff to accept empirically measurable solutions with less satisfactory theory is worth it for now.

We also expect improvements on the shortcomings as progress continues, as well as valuable cross-pollination between mechanism design theory and the deep learning approaches.

Outlook

Exploring Spaces of Other Mechanisms

More recently, a new work on two-sided matching mechanisms uses deep learning to explore the space of possible tradeoffs regarding two properties, strategyproofness and stability, which we know can not hold simultaneously for this type of mechanism. Further examples where similar techniques might be useful exist, e.g. analyzing the tradeoff space between individual rationality, balanced budget, strategyproofness and economic efficiency in the case of double auctions.

Solutions for Complex or Composed Mechanisms

We think, as methods are becoming better understood, as well as more efficient, more and more complex mechanism types will become tractable to be tackled with the above techniques, e.g. different types of markets, or supply-chain auctions. It is also imaginable that, further down the line, more generalized techniques of this kind might be used to study, or aid, the sequential and parallel composition of (different types of) mechanisms.

Why Should People In Other Areas Care About Deep Learning?

Finally, we want to fit the use of DL for mechanism design in the larger context of deep learning. There are many fields and tasks, especially in scientific computing, which don’t fit neatly into the typical story of ML, but do have a use for function approximators. And in these areas, deep nets have also proven to work particularly well – from quantum chemistry to approximately solving differential equations. We see deep learning for mechanism design as part of this trend, and we expect it to continue – when people need to approximate functions, and the tools and techniques that have come from deep learning will be an increasingly good and feasible choice.

Why Should Deep Learning People Care About Mechanism Design?

As discussed above, there is ample motivation to study the application of deep learning techniques to mechanism design, but what about the other way around?

One problem that practitioners from the deep learning field might be familiar with, are settings in which individuals try to game certain classifiers by manipulating their features. A line of inquiry into strategic classification has lead to methods of designing classifiers which are robust to being gamed this way, by coming up with strategyproof solutions.

Another field that has gained relevance in recent years is distributed, federated or multi-party machine learning. Here questions emerge of how to balance costs that individuals incur in resources like bandwidth, storage and privacy when they share data with the utility they receive from e.g. higher model accuracy.

Mechanism design and deep learning can also be complimentary in solving problems which exist in both fields, e.g. problems of algorithmic fairness, by having the successes and shortcomings of both fields inform the development of a unified approach.

As a further introduction to the foundational concepts of mechanism design we recommend Tim Roughgarden’s Twenty Lectures on Algorithmic Game Theory.

Interactions between computer science and mechanism design have been going on for many decades now. But the use of powerful computational tools from deep learning for mechanism design is just beginning – and already has some excellent results. We hope that this post can make researchers from both areas feel curious about the other – there is a lot of room for contributions going both ways.

-

Suppose some non-IC mechanism has a non-truthful Bayes-Nash equilibrium (dominant-strategy equilibrium in the case of DSIC), where each bidder might make some complicated choice of move depending on their type. The auctioneer can always make an equivalent BNIC (respectively DSIC) mechanism by determining the correct strategy for each bidder as a function of their valuation, and then just asking bidders to truthfully report their type and playing the correct strategy for them. ↩

-

This has actually been used in practice by large companies. ↩